Extremely powerful cosmic rays are raining down on us. No one knows where they come from.

You may think the greatest, most perplexing mysteries of the universe exist way out there, at the edge of a black hole, or inside an exploding star.

No, great mysteries of the universe surround us, all the time. They even permeate us, sailing straight through our bodies. One such mystery is cosmic rays, made of tiny bits of atoms. These rays, which are passing through us at this very moment, are not harmful to us or any other life on the surface of Earth.

But some carry so much energy that physicists are baffled by what object in the universe could have created them. Many are much too powerful to have originated from our sun. Many are much too powerful to have originated from an exploding star. Because cosmic rays don’t often travel in a straight line, we don’t even know where in the night sky they are coming from.

The answer to the mystery of cosmic rays could involve objects and physical phenomena in the universe that no one has ever seen or recorded before. And physicists have several enormous experiments around the world underway now devoted to cracking the case.

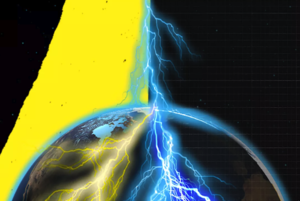

Though we don’t know where they come from, or how they get here, we can see what happens when these cosmic rays hit our planet’s atmosphere at nearly the speed of light.

Cosmic rays are messengers from the broader universe; a reminder we’re a part of it, and a reminder that there’s still a great deal of mystery out there. Let’s take a close look at these astonishing particles, raining on Earth from afar.

Smashing into our atmosphere

When the particles in cosmic rays collide with the atoms in at the top of the atmosphere, they burst, tearing apart atoms in a violent collision. The particles from that explosion then keep bursting apart other bits of matter, in a snowballing chain reaction. Some of this atomic shrapnel even hits the ground.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18311156/cosmic_rays_diagram.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18314550/cosmic_rays_atmosphere.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox; NASA

It’s possible to see this in action by building what’s called a cloud chamber out of a glass jar, felt, dry ice, and isopropyl alcohol (i.e. rubbing alcohol). You soak the felt in the alcohol, and the dry ice (which is super-cold solid carbon dioxide) cools down the alcohol vapor, which is streaming down from the felt. That creates a cloud of alcohol vapor.

In this chamber, you can see the cosmic rays, particularly those from a particle called a muon. Muons are like electrons, but a bit heavier. Every square centimeter of Earth at sea level, including the space at the top of your head, gets hit by one muon every minute.

Like electrons, muons carry a negative charge. When the muons zip through the alcohol cloud, they ionize (charge) the air they pass through. The charge in the air attracts the alcohol vapor, and it condenses into droplets. And those droplets then trace the path the cosmic rays made through the chamber.

When you see the paths these muons make, think about this: These subatomic particles rocket down to Earth at 98 percent the speed of light.

They move so fast, they experience the time dilation predicted by Einstein’s theory of special relativity. They’re supposed to decay — i.e. break apart into smaller components, electrons, and neutrinos — in just 2.2 microseconds, which would mean they’d barely get 2,000 feet down from the top of the atmosphere before dying. But because they’re moving so fast, relative to us, they age 22 times more slowly. (A similar thing happened to Matthew McConaughey’s character in the movie Interstellar, as he sped up his relative speed nearing a black hole.)

If Einstein’s theory weren’t true, we wouldn’t see any muons in the cloud chamber. Luckily, they are harmless, moving so fast that they don’t have the time to land an impactful punch in your body. Scientists can do some cool things with muons, like use them to photograph the inside of the Great Pyramid in Egypt.

Recall that these rays were potentially propelled by forces from beyond our solar system, by forces no physicist understands. That’s plainly awesome.

“Our theoretical physicist colleagues are perplexed” about how these particles are energized, says Charles Jui, a physicist at the University of Utah on the hunt for cosmic rays. “We also can’t figure out where they are coming from.”

Cosmic rays, explained

The mystery of cosmic rays began with their discovery in 1912. That’s when the physicist Victor Hess took a ride on a hot air balloon and discovered the amount of radiation in the atmosphere increases the higher up you go.

He was on the balloon to isolate his experiment from radiation. But it was only noisier higher up. That led him to conclude that the radiation was coming from space, and not radioactivity from rocks in the earth.

He also took this balloon ride during a total solar eclipse. With the moon blocking the sun, cosmic radiation coming from the sun ought to have been filtered out. But he still recorded some. That led him to the insight that the radiation was not coming from the sun, but from deeper in space. His discovery of cosmic rays won him the 1936 Nobel prize in physics.

The highest-energy cosmic ray particle ever recorded, called the “Oh-My-God” particle, was some 2 million times more energetic than the most souped-up proton propelled by the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

That energy, Antonella Castellina, an Italian astrophysicist with the Pierre Auger Observatory, explains, is similar to a top tennis pro hitting a ball with all their strength. Now, that doesn’t sound like a lot. But imagine all that energy squeezed into an area smaller than an atom — that’s extreme. It’s enough power to turn on a light bulb for a second or more. “Nobody knows what in the universe is able to give a subatomic particle such an energy,” she says.

More than that, scientists are baffled to how such a particle can even reach Earth. Particles with such crazy-high energies are thought to interact with the radiation leftover from the Big Bang and the creation of the universe, which ought to put the breaks on them before they reach us.

What created the “Oh-My-God” particle and similarly powerful cosmic rays is a complete, baffling mystery. (You might be thinking, why are we calling these particles “rays”? It’s a bit of a misnomer that stuck around from when they were discovered a century ago. They’re also called “astroparticles.” But cosmic rays sound cooler, so we’ll stick with that.)

Cosmic rays were discovered 100 years ago. So you might be thinking: Why can’t we figure out what’s shooting these cosmic rays at us?

Well, we do know some cosmic rays come from the sun. But the strongest ones, the most mysterious ones, come from the great way-out-there in the galaxy and universe.

The problem with looking for the sources of these very high energy cosmic rays is that the rays don’t always travel in a straight line. The various magnetic fields of the galaxy and universe deflect them, and put them on bendy paths.

Many of the cosmic rays that hit Earth — particularly the ones that come from our sun — get deflected to the poles due to Earth’s magnetic field. That’s why we have the Northern and Southern Lights near the poles.

There are a few huge projects underway to better understand where these cosmic rays come from. One involves a truly enormous block of ice at the South Pole.

An enormous block of ice at the South Pole is a giant cosmic-ray detector

There’s not much alive at the bottom of the world, except for the physicists. There, at the south pole, they’ve built the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, forged directly into the ice beneath the surface of the South Pole.

It is a 1-cubic kilometer (about 1.3 billion cubic yards) block of crystal-clear ice surrounded by sensors. These sensors are set up to detect when subatomic particles called neutrinos — which travel along with other subatomic particles in cosmic rays — crash into Earth.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18315014/ICE_CUBE_COSMIC_RAYS.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox

How it works is not so different from the cloud chamber experiment we showed you above. It’s trying to trace the path a very special type of cosmic ray — called a neutrino — makes through the observatory.

Neutrinos are different from the other components of cosmic rays in one really important way: They don’t interact with other forms of matter much at all. They don’t have any electrical charge. That means they travel through the universe in a relatively straight line, and we can trace them back to a source.

“If I shine a flashlight through a wall, the light won’t go through,” Naoko Kurahashi Neilson, a particle physicist at Drexel University, told me. “That’s because the light particles, the photons, interact with the particles in the wall and they can’t penetrate. If I had a neutrino flashlight, that stream of neutrinos would go through the wall.”

But every once in a while a neutrino — perhaps every one in 100,000 — will hit an atom in the ice at the observatory and break the atom apart.

Then something spectacular happens: The collision produces other subatomic particles, which are then propelled to a speed faster than the speed of light as they pass through the ice.

You might have heard that nothing can travel faster than light. That’s true, but only in a vacuum. The photons that make up light (a subatomic particle in their own right) actually slow down a bit when they enter a dense substance like ice. But other subatomic particles, like muons and electrons, do not slow down.

When particles are moving faster than light through a medium like ice, they glow. It’s called Cherenkov radiation. And the phenomenon is similar to that of a sonic boom. (When you go faster than the speed of sound, you produce a blast of noise.) When particles move faster than light, they leave wakes of an eerie blue light like a speedboat leaves wakes in the water. Here’s an artist’s depiction of what this all looks like. The neutrino is the tear-drop shape in gray.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11680151/2018_07_12_09_30_17.gif)

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab/Nicolle R. Fuller/NSF/IceCube

Other observatories looking for cosmic rays are similarly enormous

The Pierre Auger Observatory, where Castellina works, uses an array of 1,600 tanks, each filled with 3,000 gallons of water. The tanks are spread across more than 1,000 square miles in Mendoza, Argentina.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18314870/AUGER_MAP.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox

The tanks work like the block of ice at the South Pole. But instead of using ice to record cosmic rays, they use water. The tanks are completely pitch black inside. But when cosmic rays — more than just neutrinos — enter the tanks, they cause little bursts of light, via Cherenkov radiation, as they exceed the speed of light in water.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18312355/AUGER_TANK_COSMIC_RAYS.jpg) Javier Zarracina/Vox

Javier Zarracina/Vox

If many of the tanks record a burst of cosmic rays at the same time, the scientists can then work backward and figure out the energy of the particle that hit at the top of the atmosphere. They can also make a rough guess on where in the sky the particle was shot from.

In the Northern Hemisphere, there’s a similar experiment in Utah called the telescope array. Like the tanks in South America, the array in Utah has a series of detectors spread out over an enormous area. Currently, it takes up about 300 square miles, but there’s an upgrade in the works expanding it up to 1,200 square miles. (The larger the area, the greater the chance to spot the most elusive and powerful cosmic rays.)

The detectors in Utah are made up of super-clear acrylic plastic, and are housed in units that kind of look like hospital beds.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18314884/cosmic_rays_utah_scintillator.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox

If many of the detectors record a hit in sequence (think of the particles all hitting the ground around the same time like shotgun pellets on a target board), “you can reconstruct the direction” from which they came, says Jui, the University of Utah physicist who works on the array.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18314354/UTAH_cosmic_detector.jpg)

Javier Zarracina/Vox

The observatory can also do something cool. On very clear, dark nights in the Utah desert, it can actually see the faint trails of cosmic rays lighting up in our atmosphere.

“The idea is that you can see the air shower develop in the atmosphere using ultraviolet cameras,” Jui says. “These are cameras that are taking videos, over a few microseconds, ten frames a microsecond [that’s extreme slow motion], and then you can actually see the extended line in the sky, and measure the [cosmic ray’s] energy from that.”

You can help the search for cosmic rays

With enough data on these high-energy cosmic rays, scientists hope to one day better pinpoint where in the sky they come from.

The problem is that right now, they just don’t have enough observations of the most powerful cosmic rays.

It’s going to take some time because the most powerful cosmic rays don’t pass through detectors all too frequently: Every square kilometer of Earth only sees about one of these particles per century. And to account for the fact that these rays don’t often travel in a straight line, it’s going to take a mountain of data.

But already, we have some clues. The Pierre Auger observatory has some (not yet conclusive) data that some of these high-energy particles come from starburst galaxies, which are galaxies that are forming stars at a very fast rate. Jui’s group has concluded that about a quarter of the most powerful cosmic rays observed come from a circle about 6 percent the size of the night sky, near the Big Dipper constellation. But that’s an enormous area of space, and there’s no obvious smoking gun in the region.

More clues continue to trickle in. Last summer, scientists at the IceCube observatory published exciting evidence that galaxies called blazars generate some of these high-energy particles. Blazars have supermassive black holes at the center of them that rip apart matter into its constituent parts, and then blast subatomic particles off like a laser cannon into space.

Here’s an artist’s depiction that is very, very not to scale, showing a blazar shooting a beam of cosmic rays at Earth.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11680313/BlazarNeutrino2_1920x1080_M__1_.jpg)

IceCube/NASA

The current results can’t yet explain the most powerful cosmic rays detected on record. They also need to be repeated.

There is also the possibility that some of the rays are produced by forces and objects we currently don’t know about — or interact with mysterious things like dark matter, in ways we don’t yet understand. It could be aliens, but I doubt it.

What scientists need is more data, more observations to be able to pinpoint the sources in the sky these particles are coming from.

And soon, you can get in on the search. Your phone can be turned into a cosmic ray detector. Daniel Whiteson is a physicist at the University of California Irvine who has been working on a crowd-sourced cosmic ray project. It’s called Crayfis (Cosmic RAYs Found In Smartphones).

“The number of particles that are hitting the atmosphere with crazy energies, is really large. It’s in the millions [per year],” Whiteson says. But observatories like the Pierre Auger — though huge — aren’t large enough to spot most of them. “If we could build a big enough telescope covering huge swaths of land, we could collect a lot of data really quickly.”

That’s where the smartphones come in. The camera in your phone works because photons — the subatomic particle that constitute light — activates a sensor at the back of the lens. Cosmic rays can activate the sensor too. (Every once in a while, too, a cosmic ray can interfere with a microprocessor and cause a computer to crash.)

“If you put your phone camera face down, most of the [light] is blocked, and you’d get a black picture,” he explains. “But particles from space, will pass right through your phone, ceiling, or wall, and hit the [camera sensor], and will leave a trace.”

The hope is that millions of users can turn the app on at night while they are asleep, and it will look for these cosmic rays. With enough phones, Whiteson hopes, he and his colleagues can get a better picture of where cosmic rays come from. The project isn’t quite off the ground yet. But you can sign up now to become a beta tester when the app is ready.

Physicists aren’t going to give up anytime soon. The existence of high-energy cosmic rays tells us our understanding of the universe is woefully incomplete.

“This is some of the most violent phenomena” in the universe, Jui says. Don’t you want to find out what causes it?