PACE yourself

When Katy Rodriguez Wimberly came to UCI in the fall of 2016 to start her PhD in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, she came straight from a summer program offered by the university called “Competitive Edge.” The program gave her six weeks to get to know UCI, and to meet faculty and fellow grad students who gave her tips on how to do well in the years to come. The connections she made that summer helped her feel like she belonged in grad school, and that she was a part of the UCI community.

But when Competitive Edge ended and the school year began, that feeling of community all but vanished. “The only peer mentoring was that every first-year graduate student was assigned a more senior graduate student to have coffee with. “‘Here’s a coffee card, go chat’,” Rodriguez Wimberly recalls someone telling her. “That was it.”

Arianna Long, a third-year Physics and Astronomy grad student, did Competitive Edge the following year in 2017. Rodriguez Wimberly was one of her mentors, and, Long says, “it was wonderful and rich and structured, and I feel like I got so much out of it.”

But then the coffee card came, the school year started, and the richness vanished. “It was so deflating,” says Long. “Lots of mentors would just give the coffee card to their mentees and be like ‘here you go,’ and then evaporate.” Long did meet with her coffee card mentor, and she says the meeting was “nice,” but it became clear to her that her mentor did not have the training they needed to, well, be a mentor. “It felt like being dropped in an ice bucket,” she says.

Rodriguez Wimberly and Long stayed friends after they met in Competitive Edge, and they would spend hours talking about the swarm of questions that graduate school can be for a new student. How much should I be working every week? Are classes more important than research? How do I prepare for my qualifying exams?

Back then, there were few good answers.

“I’m over here just so scared that I was gunna get kicked out of the program because I was not gunna be able to pass the qual,” recalls Rodriguez Wimberly, who along with Long discovered they were not the only students struggling. Francisco Mercado, who started at UCI at the same time as Long, found when he began at UCI that he was completely unprepared for the level of coursework that awaited him. “That was one of the biggest stresses I had coming in,” he says. “Eventually, by the end of the first year, I was sort of figuring out what was going on.”

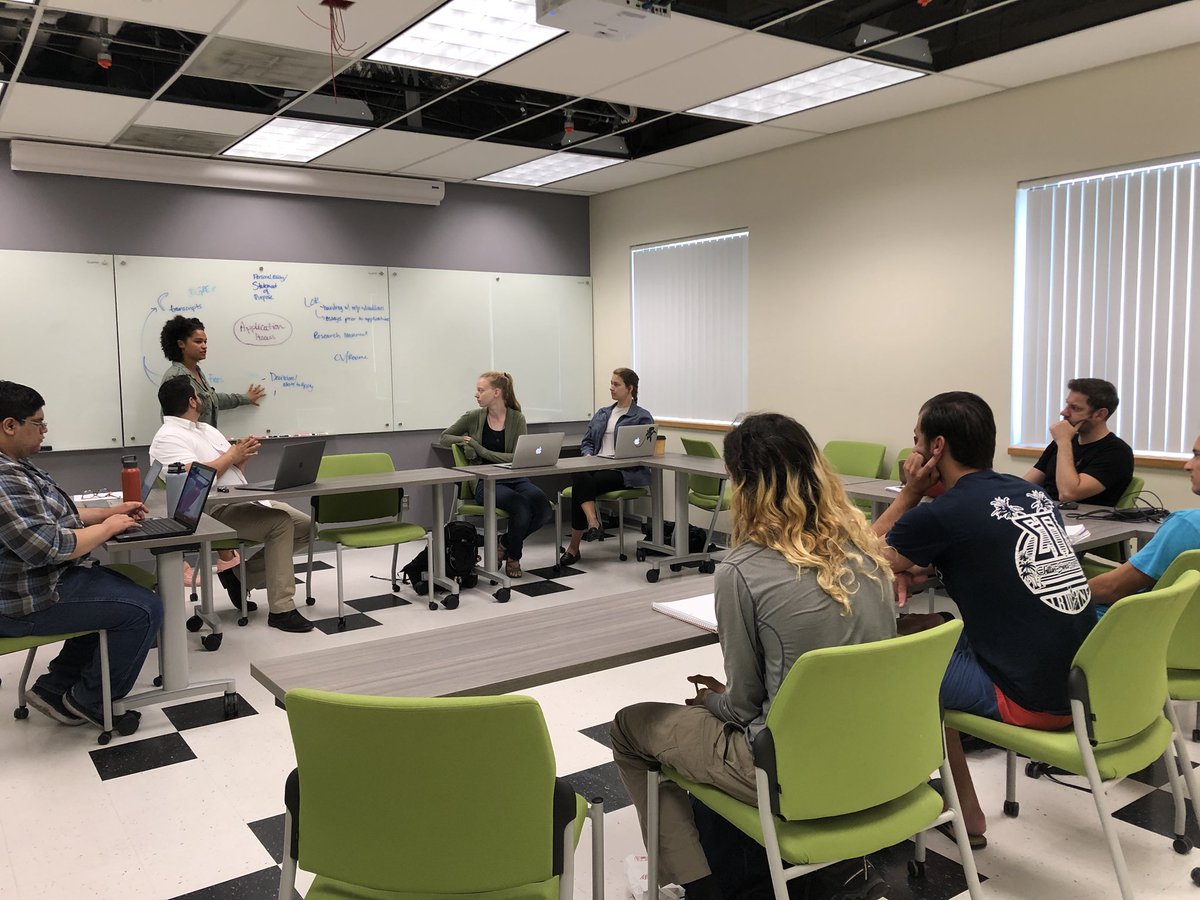

Now, three years later, things are different. Out of the ice bucket that students like Rodriguez Wimberly, Long and Mercado fell into arose Physics & Astronomy Community Excellence, or PACE, which is a cadre of mentors who guide students through the icy questions that can define a first-year grad student’s life. The coffee card meetings remain, but now anyone who wants to mentor a new grad student are required to take a three-hour mentoring course given by PACE.

First-year graduate students also answer a questionnaire, and PACE uses their answers to pair them with mentors who are a good match.

Now, once a month on Fridays, PACE mentors take over one of the classes that all first-year grad students have to take. They call the monthly session “Fire Up Fridays,” and PACE leaders like Long and Rodriguez Wimberly, who are PACE’s co-organizers, use the class to talk about the questions that once plagued them — like how to face quals. “I can just see kind of the stress melt away from some of the first-years, and I’m like ‘oh, I so wish that had been me’,” Rodriguez Wimberly says.

PACE mentors talk about work-life balance with mentees, and they field topics like the stereotype that it’s normal for grad students to work relentless hours, sometimes sleeping at work so they can get more work done. “If you’re just talking to faculty, they’re just gunna be like ‘do as much as you can’,” says Long. But PACE provides time and space for students to understand that their health does not need to be a slave to school.

PACE is only three years old, but Long and Rodriguez Wimberly already see the program’s legacy taking shape. Every mentor that the two recruited last August, Long explains, was either a first-year student who went through PACE, or was a mentor returning to the program. That was “the moment that I realized we’re doing something awesome,” Long says.

Rodriguez Wimberly felt PACE’s legacy when she shared a stress-relief tip with students about to face their qualifying exams. “‘I lived off Hot Cheetos’,” she told them. “I was on my Hot Cheeto soap box telling everybody: ‘just comfort eat, just get through it, you’ll be OK.’” One mentee took what she said to heart, and the mentee drank Slurpee upon Slurpee in the lead-up to her exams. Then, when that mentee became a mentor herself, and when first-years asked her how to prepare for quals, she told them: “‘comfort food, eat comfort food’,” recalls Rodriguez Wimberly, who after seeing her own words echoing through generations of students, thought: “‘This is it, we’ve done it!’” she says.

PACE is not perfect. Mentors receive no pay for what they do, and Long and Rodriguez Wimberly one day want to change that.

For now, though, the ice is out of the bucket.