Could the Sahara ever be green again?

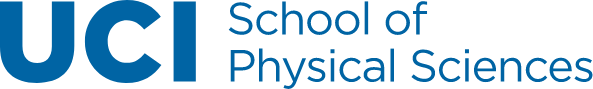

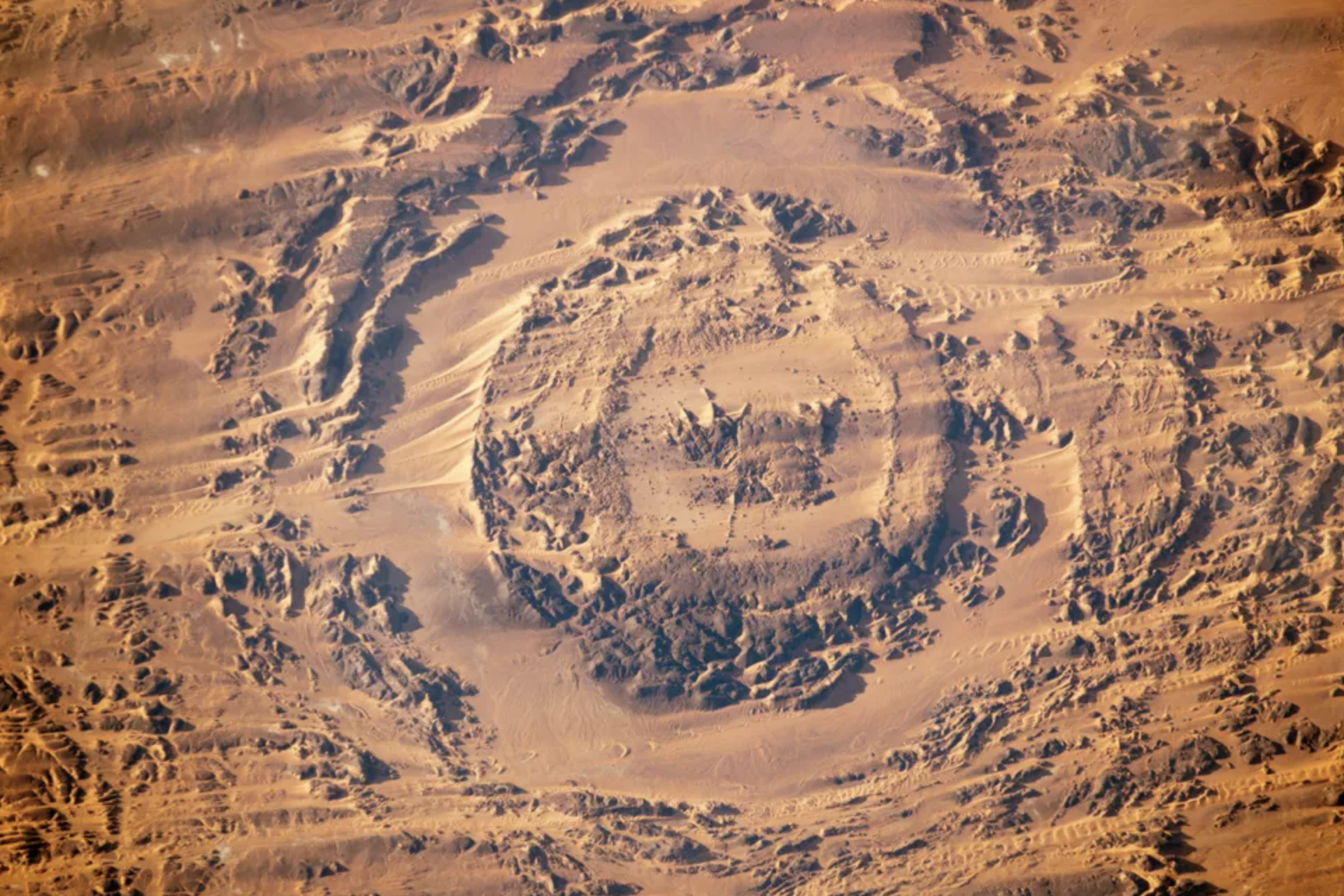

The central Sahara Desert. Once, the Sahara was a lush, verdant place. Could it ever be again?

Sometime between 11,000 and 5,000 years ago, after the last ice age ended, the Sahara Desert transformed. Green vegetation grew atop the sandy dunes and increased rainfall turned arid caverns into lakes. About 3.5 million square miles (9 million square kilometers) of Northern Africa turned green, drawing in animals such as hippos, antelopes, elephants and aurochs (wild ancestors of domesticated cattle), who feasted on its thriving grasses and shrubs. This lush paradise is long gone, but could it ever return?

In short, the answer is yes. The Green Sahara, also known as the African Humid Period, was caused by the Earth's constantly changing orbital rotation around its axis, a pattern that repeats itself every 23,000 years, according to Kathleen Johnson, an associate professor of Earth systems at the University of California Irvine.

However, because of a wildcard — human-caused greenhouse gas emissions that have led to runaway climate change — it's unclear when the Sahara, currently the world's largest hot desert, will turn a new green leaf.

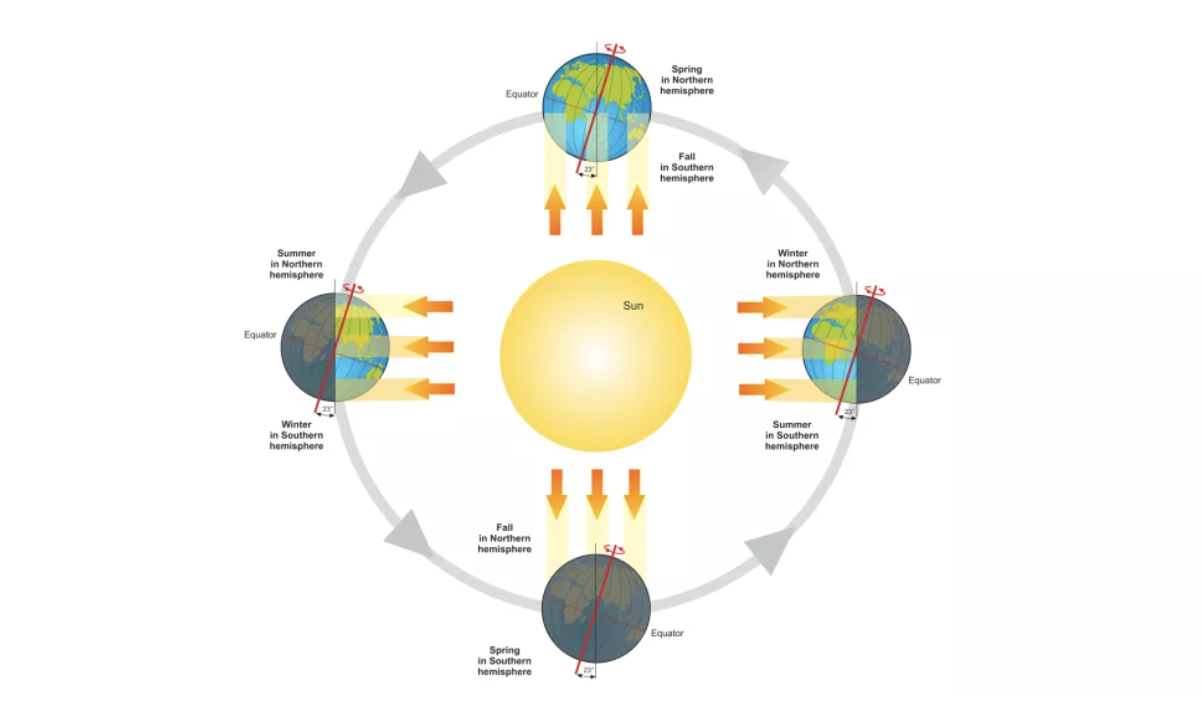

The Sahara's green shift happened because Earth's tilt changed. About 8,000 years ago, the tilt began moving from about 24.1 degrees to the current day 23.5 degrees, Space.com, a Live Science sister site, previously reported. That tilt variation made a big difference; right now, the Northern Hemisphere is closest to the sun during the winter months. (This may sound counterintuitive, but because of the current tilt, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun during the winter season.) During the Green Sahara, however, the Northern Hemisphere was closest to the sun during the summer.

This led to an increase in solar radiation (in other words, heat) in Earth's Northern Hemisphere during the summer months. The rise in solar radiation amplified the African monsoon, a seasonal wind shift over the region caused by temperature differences between the land and ocean. The increased heat over the Sahara created a low pressure system that ushered moisture from the Atlantic Ocean into the barren desert. (Usually, the wind blows from dry land toward the Atlantic, spreading dust that fertilizes the Amazon rainforest and builds beaches in the Caribbean, Live Science previously reported.)

This increased moisture transformed the formerly sandy Sahara into a grass and shrub-covered steppe, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As animals there prospered, humans did too, eventually domesticating buffalo and goats and even creating an early system of symbolic art in the region, NOAA reported.

Wobbling Earth

But why did Earth's tilt change in the first place? To understand this monumental change, scientists have looked to Earth's neighbors in the solar system.

"The Earth's axial rotation is perturbed by gravitational interactions with the moon and the more massive planets that together induce periodic changes in the Earth's orbit," Peter de Menocal, the director at the Center for Climate and Life at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York, wrote in Nature. One such change is a "wobble" in the Earth's axis, he wrote.

That wobble is what positions the Northern Hemisphere closer to the sun in the summer — what researchers call a Northern Hemisphere summer insolation maximum — every 23,000 years. Based on research first published in the journal Science in 1981, scholars estimate that the Northern Hemisphere had a 7% increase in solar radiation during the Green Sahara compared with now. This increase could have escalated African monsoonal rainfall by 17% to 50%, according to a 1997 study published in the journal Science.

What's interesting to climate scientists about the Green Sahara is how abruptly it appeared and vanished. The termination of the Green Sahara took only 200 years, Johnson said. The change in solar radiation was gradual, but the landscape changed suddenly. "It's an example of abrupt climate change on a scale humans would notice," she said.

"Records from ocean sediment show [that the Green Sahara] happens repeatedly," Johnson told Live Science. The next Northern Hemisphere summer insolation maximum — when the Green Sahara could reappear — is projected to happen again about 10,000 years from now in A.D. 12000 or A.D. 13000. But what scientists can't predict is how greenhouse gases will affect this natural climate cycle.

Paleoclimate research "provides unequivocal evidence to what [humans] are doing is pretty unprecedented," Johnson said. Even if humans stop emitting greenhouse gases today, these gases would still be elevated by the year 12000. "Climate change will be superimposed onto the Earth's natural climate cycles," she said.

That said, there's geologic evidence from ocean sediments that these orbitally-paced Green Sahara events occur as far back as the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5 million years ago), including during periods when atmospheric carbon dioxide was similar to, and possibly higher, than today's levels. So, a future Green Sahara event is still highly likely in the distant future. Today's rising greenhouse gases could even have their own greening effect on the Sahara, though not to the degree of the orbital-forced changes, according to a March review published in the journal One Earth. But this idea is far from certain, due to climate model limitations.

Meanwhile, there is another way to turn parts of the Sahara into a green landscape; if massive solar and wind farms were installed there, rainfall could increase in the Sahara and its southern neighbor, the semiarid Sahel, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Science.

Wind and solar farms can increase heat and humidity in the areas around them, Live Science previously reported. An increase in precipitation, in turn, could lead vegetation growth, creating a positive feedback loop, the researchers of that study said. However, this huge undertaking has yet to be tested in the Sahara Desert, so until such a project gets funding, humans might have to wait until the year 12000 or longer to see whether the Sahara will turn green again.

Originally published on Live Science.