Recent News:

Older material can be found in the [archive].

The [media section] contains photographs and other digital material.

Toronto Sep 23, 2009.

AGU Outstanding Student Paper Award

Katrine Gorham, a recent Ph.D. from the Rowland-Blake research group, has been awarded an Outstanding Student Paper Award for her presentation at the AGU 2009 Joint Assembly in Toronto.

Termite Insecticide a Potent Greenhouse Gas

See the UCI press release here: [UCI press release]

Visit the UCI ARCTAS blog!

Our research group is participating in the NASA ARCTAS (Arctic Research of the Composition of the Troposphere from Aircraft and Satellites) airborne field campaign.

Visit the blog here: http://arctas-uci.blogspot.com/

The ARCTAS project is one of many different polar research projects that are going on during the International Polar Year. This research will help to gain a better understanding of arctic atmospheric composition, including pollution, statospheric-tropospheric exchange, and photochemistry. The field campaign has two phases: the first phase (with flights starting on April 1st) is based out of Fairbanks, Alaska, and the the second phase (which starts in June) is based out of Cold Lake, Canada. Our lab will be collecting whole air samples on board the DC-8 aircraft.

C&EN, Dec 24, 2007.

A Giant Among Chemists

Nobel Laureate F. Sherwood Rowland discusses his almost six-decade-long career as researcher and public policy advocate

By Bette Hileman

IN MANY WAYS, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry F. Sherwood Rowland is an imposing figure: He is imposing in his 6'5" height, in the breadth of his intellect, in his ability to work in cross-disciplinary areas, and in his willingness to step outside the confines of academia and effect change in the policy arena.

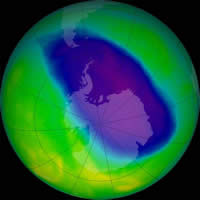

Rowland, 80, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995, along with Mario J. Molina and Paul J. Crutzen, for pioneering research on how chlorofluorocarbons destroy stratospheric ozone. By 1987, this work had led to the signing of the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer, widely considered the most successful international environmental treaty ever.

Last month, C&EN interviewed Rowland in his office at the University of California, Irvine, where he is the Bren Research Professor of Chemistry & Earth System Science.... (...)

Read the full article on C&EN's website (http://pubs.acs.org/isubscribe/journals/cen/85/i52/html/8552gov1.html) or download a pdf-print [pdf-link].

Irvine, Calif., Oct 29, 2007.

Professor Blake has been awarded the distinction of Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

In October, the AAAS Council elected 471 members as Fellows of AAAS. These individuals will be recognized for their contributions to science and technology at the Fellows Forum to be held on 16 February 2008 during the AAAS Annual Meeting in Boston. The new Fellows will receive a certificate and a blue and gold rosette as a symbol of their distinguished accomplishments.

http://www.aaas.org/aboutaaas/fellows/2007.shtml

October 8, 2007.

Delaware City Schools Inducts Professor F.S. Rowland into Hall of Honor.

[read the the full announcement here]

On October 8, the Delaware City School system celebrated an inaugural induction of Distinguished Alumni into its Hall of Honor. Three of those illustrious alumni are also notable alumni of Ohio Wesleyan.

The late William Eells `46, Sherwood Rowland `48, and the late Henry Clay “Hank” Thomson II `30 were inducted into the Delaware City Schools Distinguished Alumni Hall of Honor along with fellow Delaware alumni Esther Jo King, John Michael “Mick” Seidl, and James Tull.

Irvine, Calif., September 24, 2007.

Breath analysis offers potential for non-invasive blood sugar monitoring in diabetes

Diabetics found to have elevated methyl nitrate content in exhaled breath

http://today.uci.edu/news/release_detail.asp?key=1667

Breath-analysis testing may prove to be an effective, non-invasive method for monitoring blood sugar levels in diabetes, according to a University of California, Irvine study.

By using a chemical analysis method developed for air-pollution testing, UC Irvine chemists and pediatricians have found that children with type-1 diabetes exhale significantly higher concentrations of methyl nitrates when they are hyperglycemic.

The study heralds the potential of a breath device that can warn diabetics of high blood sugar levels and of the need for insulin. Currently, diabetics monitor blood sugar levels using devices that break the skin to attain a small blood sample. Hyperglycemia is common in type-1 diabetes mellitus.

Study results appear this week in the early online version of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Breath analysis has been showing promise as a diagnostic tool in a number of clinical areas, such as with ulcers and cystic fibrosis,” said Dr. Pietro Galassetti, a diabetes researcher with the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at UC Irvine. “While no clinical breath test yet exists for diabetes, this study shows the possibility of non-invasive methods that can help the millions who have this chronic disease.”

In the study, Galassetti, Dr. Dan Cooper and Andria Pontello of the GCRC conducted breath-analysis testing on 10 children with type-1 diabetes mellitus. The researchers took air samples during a hyperglycemic state and progressively as they increased the children’s blood insulin levels.

The breath samples were sent to the laboratory of UC Irvine chemists F. Sherwood Rowland and Donald Blake, who examined the exhaled breath using methods developed for their atmospheric chemistry work. In that work, they measure the levels of trace gases in excess of the parts-per-billion range that contribute to local and regional air pollution. Their research group is one of the few in the world recognized for its ability to measure accurately at such small amounts.

The Rowland-Blake group analyzed the children’s breath samples for more than 100 gases at parts-per-trillion levels and found methyl nitrate exhaled concentrations to be increased as much as 10 times more in diabetic children during hyperglycemia than when they had normal glucose levels. The methyl nitrate concentrations corresponded with the children’s glucose levels – the higher the glucose, the higher the exhaled methyl nitrates.

Galassetti said that during hyperglycemia, in type 1 diabetes there are more fatty acids in the blood that cause oxidative stress. Methyl nitrate is likely a by-product of this increased oxidative stress. It is commonly present in ambient air at very low concentrations, Galassetti noted, and normally appears in the exhaled breath samples of healthy subjects at parts-per-trillion levels.

“Currently, we are involved with new studies looking at the correlation of other gases with hyperglycemia and other variables, including insulin,” Galassetti said. “Eventually, we hope to put together a full exhaled gas profile of diabetes, and our efforts look promising.”

UC Irvine chemists Brian Novak and Simone Meinardi also participated in the study, which was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

About the University of California, Irvine: The University of California, Irvine is a top-ranked university dedicated to research, scholarship and community service. Founded in 1965, UCI is among the fastest-growing University of California campuses, with more than 25,000 undergraduate and graduate students and about 1,800 faculty members. The second-largest employer in dynamic Orange County, UCI contributes an annual economic impact of $3.7 billion. For more UCI news, visit www.today.uci.edu.

News Radio: UCI maintains on campus an ISDN line for conducting interviews with its faculty and experts. The use of this line is available free-of-charge to radio news programs/stations who wish to interview UCI faculty and experts. Use of the ISDN line is subject to availability and approval by the university.

Detecting disease by breath?

Led by Don Blake, UCI scientists look for biomarkers of disease in the gases humans exhale.

By GARY ROBBINS

The Orange County Register

The idea is simple: Take breath samples from people to see if the gases in their lungs can be linked to specific diseases, such as diabetes. But will the plan work? Can the hundreds of gases we exhale be widely used to diagnose our health?

The question has begun to get lots of attention at UC Irvine from many people, ranging from atmospheric chemist Don Blake to pediatrician-bioengineer Dan Cooper to geneticist Doug Wallace.

The work is being led by Blake, who is known internationally for the accuracy with which he identifies and measures gases. We spoke to Blake about where the research is headed.

Q: Why do scientists believe it might be possible to determine that a person has a specific disease by analyzing the gases they exhale?

A: At the moment, physicians can figure out if a person has a certain disease by examining their blood or their DNA. You also can tell a lot by analyzing urine. We might be able to do the same by looking at gases. People exhale hundreds – maybe thousands – of different gases. Specific amounts or combinations of gases might be biomarkers for illness.

There is a disease whose common name is "maple syrup disease" because the breath of the patient smells like maple syrup. Diabetics, at times, will have the smell of acetone on their breath. So it's not a real stretch to think that at very low levels, some gases could be markers.

If this is true, we would have a much less invasive way of examining people. Right now, it's not unusual for an old person to develop bruises on their skin after they've given a blood sample. It would be great if we could avoid that by analyzing their breath instead of their blood.

Also, we now know that many diseases cause increased stress and inflammation, and we increasingly predict that breath biomarkers will be good at detecting the results of inflammation.

Q: This is a fairly new field. Have any reliable breath-analysis tests been developed so far for disease?

A: There are two currently being used. One is to determine if a person is giving off high levels of hydrogen, which is a sign of the bacteria H. pylori, which causes some intestinal ulcers. Another is an isotope study to determine lactose intolerance. Also, nitric oxide breath measures are common in asthma patients.

Mike Kamboures, a former graduate student at UCI, cultured six to eight bacteria that commonly colonize the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. He found that each of the eight bacteria gave off lots of gases. His study suggests that there's a chance we will identify a set of gasses, or a set of gas concentrations, that are produced by bacteria directly linked to cystic fibrosis, which damages people's lungs.

Other lung illnesses may fall into this same category where breath analysis can identify specific bacteria that are causing problems.

Q: How good are scientists at identifying telltale gases from the body?

A: If you stop and put gasoline in your car prior to coming to UCI for a breath sample, we can tell you inhaled gasoline fumes within the last hour. If you have asthma and use a bronchial inhaler, we can see the propellant in your breath for weeks.

Q: Is there a downside here? Could insurance companies use breath gas tests to identify diseases a person might develop later in life and therefore deny them a policy?

A: I imagine anything is possible, but I would hope this wouldn't happen. They now have some forms of genetic testing and I don't think insurance companies hold that against potential clients. However, I was denied life insurance because the routine blood test I was given showed that my PSA (prostate-specific antigen) was above normal.

Q: Humans have about 23,000 genes. The number of gases in their lungs is far smaller, but it's still sizable. Will it be hard to conclusively determine which gases, if any, are specifically linked to disease?

A: It won't be easy and will require lots of subjects, both with specific diseases and controls. It's sort of like fingerprinting. It took time to catch on and look at where it is today. DNA fingerprinting is the same. So once the concept is proven I anticipate there will be a significant increase in the amount of research that is directed to exhaled breath gas analysis.

Q: A few years ago, you were successfully treated for prostate cancer. At the time you took samples of the gases you exhaled. Was that just an intuitive shot at trying to find a gas linked to that disease?

A: That was the scientist side of me – my kids would say it's because I'm a nerd – that wondered if my breath gases would be different once the cancerous prostate was removed. There may have been gases that changed but we have not identified them.

However, about four weeks after surgery, I came down with an infection as a result of the surgery – I was still taking my daily breath samples that started two months earlier – and the antibiotics clearly affected the production of some gases, and one in particular. Dan Cooper thought the cancer I had was growing slowly enough that it would be difficult to observe changes in breath gases. He has talked about collecting breath from subjects who have much more aggressive cancer, and in those he thinks we might be able to identify one or more gases that aren't present in controls.

Q: Forecasting the future is risky. But do you have a sense of where this avenue of research might be in five years?

A: I think the sky is the limit. Other groups involved in breath analysis are generally clinicians and thus aren't likely to have been trained in gas analysis. We on the other hand have been quantifying gases in air since the 1970s. I am convinced that our very sensitive analytical instruments, coupled with the collection of companion samples, is going to really move the field of breath gas analysis ahead. One more advantage we have is our collaborations with top scientists and physicians here at UCI. There is a lot of translational science going on here, and it's very exciting to be part of it.

Q: You're a chemist. How are you getting clinicians involved?

A: It's the other way around. Dr. Cooper, the director of the General Clinical Research Center, contacted me in 2001 asking if I would be interested in working on breath analysis studies. This is the university setting at its best.

Contact the writer: Register science editor Gary Robbins can be reached at 714-796-7970 or grobbins@ocregister.com. Read his daily science blog at blogs.ocregister.com.

Thursday, April 12, 2007

Celebration to honor chemistry department as nurturer of breakthrough discoveries

UC Irvine’s Department of Chemistry presents “Health of the Atmosphere,” a panel discussion featuring F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, recipients of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, and Ralph Cicerone, president of the National Academy of Sciences and chancellor emeritus of UCI. This discussion is part of the Celebration of Excellence, honoring the chemistry department for receiving a Chemical Breakthroughs Awar d from the American Chemical Society.

d from the American Chemical Society.

DATE: Thursday, April 12, 2007 TIME: 5 p.m.

LOCATION: Lucille Kuehn Auditorium, Humanities Instructional Building, UCI campus

BACKGROUND: The Department of Chemistry received a Chemical Breakthroughs Award in 2006 from the American Chemical Society’s Division of the History of Chemistry. This new ACS award recognized seven universities and two companies for discoveries over the past century that had significant long-term impacts. The award is unique because it honors the department where the breakthrough occurred, recognizing that environment is crucial to nurturing great discoveries. UCI was honored for the 1974 Nature paper by Rowland and Molina that linked chlorofluorocarbons to the depletion of the Earth’s ozone layer. The finding was controversial at first, but it ultimately led to a world ban on CFCs. Rowland, now the Donald Bren Research Professor of Chemistry and Earth System Science at UCI, advises world leaders on the impact and dangers of ozone depletion and global warming. Molina, a postdoctoral researcher under Rowland when the discovery was made, now is a chemistry professor at the University of California, San Diego. UCI’s Department of Chemistry was founded in 1965, with Rowland as its original chair. It is now among the top 20 chemistry departments in the nation, leads research in all major areas of modern chemistry, and is one of the largest producers of chemists in the nation.

Irvine, Calif., November 20, 2006.

Level of Important Greenhouse Gas has Stopped Growing

[download press release]

Seven-Year Stabilization of Methane May Slow Global Warming, UCI Scientists Say

For immediate release

From The university of california, irvine

Contact:

Jennifer Fitzenberger

949-824-3969

jfitzen@uci.edu

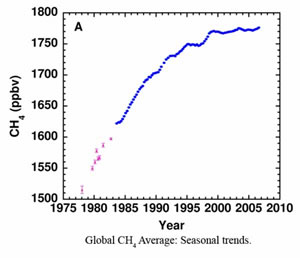

Irvine, Calif., Nov., 2006 — Scientists at UC Irvine have determined that levels of atmospheric methane –an influential greenhouse gas – have stayed nearly flat for the past seven years, which follows a rise that spanned at least two decades.

This finding indicates that methane may no longer be as large a global warming threat as previously thought, and it provides evidence that methane levels can be controlled. Scientists also found that pulses of increased methane were paralleled by increases of ethane, a gas known to be emitted during fires. This is further indication that methane is formed during biomass burning, and that large-scale fires can be a big source of atmospheric methane.

Professors F. Sherwood Rowland and Donald R. Blake, along with researchers Isobel J. Simpson and Simone Meinardi, believe one reason for the slowdown in methane concentration growth may be leak-preventing repairs made to oil and gas lines and storage facilities, which can release methane into the atmosphere. Other reasons may include a slower growth or decrease in methane emissions from coal mining, rice paddies, and natural gas production.

“If one really tightens emissions, the amount of methane in the atmosphere 10 years from now could be less than it is today. We will gain some ground on global warming if methane is not as large a contributor in the future as it has been in the past century,” said Rowland, Donald Bren Research Professor of Chemistry and Earth System Science, and co-recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize for discovering that chlorofluorocarbons in products such as aerosol sprays and coolants were damaging the Earth’s protective ozone layer.

The methane research will be published in the Nov. 23 online edition of Geophysical Research Letters.

Methane, the major ingredient in natural gas, warms the atmosphere through the greenhouse effect and helps form ozone, an ingredient in smog. Since the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s, atmospheric methane has more than doubled. About two-thirds of methane emissions can be traced to human activities such as fossil-fuel extraction, rice paddies, landfills and cattle. Methane also is produced by termites and wetlands.

Scientists in the Rowland-Blake lab use canisters to collect sea-level air in locations from northern Alaska to southern New Zealand. Then, they measure the amount of methane in each canister and calculate a global average.

From December 1998 to December 2005, the samples showed a near-zero growth of methane, ranging from a 0.2 percent decrease per year to a 0.3 percent gain. From 1978 to 1987, the amount of methane in the global troposphere increased by 11 percent – a more than 1 percent increase each year. In the late 1980s, the growth rate slowed to between 0.3 percent and 0.6 percent per year. It continued to decline into the 1990s, but with a few sharp upward fluctuations, which scientists have linked to non-cyclical events such as the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991 and the Indonesian and boreal wildfires in 1997 and 1998.

Along with methane, the UC Irvine scientists also measured levels of other gases, including ethane, a by-product of petroleum refining that also is formed during biomass burning, and perchloroethylene, a chlorinated solvent often used in the dry cleaning process. Ethane levels followed the peaks and valleys of methane over time, but perchloroethylene had a different pattern. This finding provides evidence that biomass burning, on occasion, as in Indonesia in 1997 and Russia in 1998, can be a large source of this greenhouse gas.

The researchers say there is no reason to believe that methane levels will remain stable in the future, but the fact that leveling off is occurring now indicates that society can do something about global warming. Methane has an atmospheric lifetime of about eight years. Carbon dioxide – the main greenhouse gas that is produced by burning fossil fuels for power generation and transportation – can last a century and has been accumulating steadily in the atmosphere.

“If carbon dioxide levels were the same today as they were in 2000, the global warming discussion would leave the front page. But to stabilize this greenhouse gas, we would have to cut way back on emissions,” Rowland said. “Methane is not as significant a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide, but its effects are important. The world needs to work hard to reduce the yearly emissions of methane and carbon dioxide.”

NASA and the Gary Comer Abrupt Climate Change Fellowship supported this research.

About the University of California, Irvine: The University of California, Irvine is a top-ranked university dedicated to research, scholarship and community service. Founded in 1965, UCI is among the fastest-growing University of California campuses, with more than 24,000 undergraduate and graduate students and about 1,400 faculty members. The second-largest employer in dynamic Orange County, UCI contributes an annual economic impact of $3.3 billion. For more UCI news, visit www.today.uci.edu.

Television: UCI has a broadcast studio available for live or taped interviews. For more information, visit www.today.uci.edu/broadcast.

News Radio: UCI maintains on campus an ISDN line for conducting interviews with its faculty and experts. The use of this line is available free-of-charge to radio news programs/stations who wish to interview UCI faculty and experts. Use of the ISDN line is subject to availability and approval by the university.

###

UCI maintains an online directory of faculty available as experts to the media. To access, visit www.today.uci.edu/experts.

[Top] [News Archive]

News Archive:

September 23, 2009: "AGU Outstanding Student Paper Award"

January 21, 2009: "Termite Insecticide a Potent Greenhouse Gas"

March 31, 2008: "Visit the UCI ARCTAS blog!"

December 24, 2007: "A Giant Among Chemists"

October 29, 2007: "Professor Blake Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)"

October 7, 2007: "Delaware City Schools Inducts Professor F.S. Rowland into Hall of Honor."

September 24, 2007: "Breath analysis offers potential for non-invasive blood sugar monitoring in diabetes"

April 12, 2007: "Celebration to honor chemistry department as nurturer of breakthrough discoveries"

January 22, 2007: "Detecting disease by breath?"

November 2006: "Level of Important Greenhouse Gas has Stopped Growing"