Next: About this document ...

Key Points on Chapter 15: Fluid Mechanics

- Pressure is force per unit .

- Pressure just depends on the in the fluid.

- The force on an object is an upward force

produced by the liquid.

- The buoyant force is equal to the of

the fluid displaced by the object.

- Fluid flows in a narrower pipe.

- Moving fluids exert pressure than

stationary fluids.

Lecture on Chapter 15: Fluid Mechanics

Discuss Syllabus.

States of Matter

Matter is normally classified as being in one of 3 states: solid, liquid,

or gas. A solid maintains its volume and shape. A liquid has a definite

volume but assumes the shape of its container. A gas assumes the volume

and shape of its container. We've all heard of these catagories, but

not everything can be easily put into one of these catagories. For

example, what about you? Your bones are solid, and your blood is a

liquid (suspension). But what about your flesh? What about sand?

Each grain is a solid but pour a pile of sand into a bucket and

it assumes the shape of its container like a liquid. Setting these

netteling questions aside, let us consider fluids. A fluid is a

collection of molecules that are randomly arranged and held

together by weak cohesive forces between molecules and by forces

exerted by the walls of a container. Both liquids and gases are

fluids.

Pressure

Suppose a force is applied to the surface of an object with components

parallel and perpendicular to the surface. Assume that the object does

not slide. Then the force parallel to the surface may cause the object

to distort. Do this to a book. The force parallel to the surface

is called a shearing force or a shear force. A fluid cannot sustain

a shear force. If you put your hand on the surface of a pool of water

and move your hand parallel to the surface, your hand will slide along

the surface. You will not be able to distort the water in the same

way as the book. This provides an operational definition of a fluid;

a fluid cannot sustain an infinitely slow shear force. If the

shear force is fast enough, the water can display some elasticity.

For example, consider skipping a stone across a pond. But let's just

consider the slow case. Since a fluid cannot sustain a (slow) shear, let's

ignore the shear force.

Key Point: Pressure is force per unit .

This leaves the force that is perpendicular to the surface. Suppose

the fluid is in a container. The fluid exerts a force

on the walls of the container because the molecules of the fluid

collide and bounce off the walls. By the impulse-momentum

theorem and Newton's third law, each collision exerts a force

on the wall. There are a huge number of collisions every second

resulting in a constant macroscopic force. The force is spread over

the area of the wall. Pressure is defined as the ratio of

the force to the area:

|

(1) |

Pressure has units of N/m . Another name of this is the pascal (Pa):

. Another name of this is the pascal (Pa):

|

(2) |

Force and pressure are 2 different things. Force is a vector; it

has a direction. Pressure is a scalar (a number); it doesn't

have a direction. A small amount of force

applied to a very tiny area can produce a large pressure. Consider

a hypodermic needle which easily punctures your skin. Contrast this

with lying on a bed of nails. If you lie on 1 nail, you get impaled.

But if you lie on a steel mattress, there is no problem. Even if

you lie on a bed of nails, your weight is distributed over the nails

and the force per unit area or pressure is small. Snow shoes,

skis and snowboards work this way. So does a surfboard. You can't

stand on water but you can stand on a surfboard and slide down

the face of a wave because the board distributes the force of your

weight over the area of the board. The atmosphere produces

pressure. Atmospheric pressure is given by

|

(3) |

Atmospheric pressure is what allows suction cups to work. You press

the cup onto a flat surface which pushes the air out from under the

cup. When you let go of the cup, it tries to spring back. There is not

much air under the cup so it doesn't apply much pressure to the underside

of the cup. The atmospheric pressure outside the cup is much stronger,

so it pushes the cup against the flat surface.

Variation of Pressure with Depth

Key Point: Pressure just depends on the in

the fluid.

Pressure in a fluid varies with the depth of the fluid. The deeper

down you go in the ocean, the higher the water pressure because

there is more water on top of you and water weighs a lot (8 pounds

per gallon). This is why deep sea divers must wear diving suits.

The higher up you go in the atmosphere, the lower the atmospheric

pressure. This is why airplanes must pressurize their cabins.

Also the air becomes less dense at high altitudes, so your lungs

would not get enough oxygen if the cabin were not pressurized.

=3.0 true in

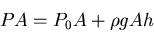

We can derive a mathematical relation showing how the pressure

varies with depth. Consider a liquid of density  at rest.

Consider a portion of the liquid contained within an imaginary

cylinder of cross-sectional area

at rest.

Consider a portion of the liquid contained within an imaginary

cylinder of cross-sectional area  . The height of the cylinder

is

. The height of the cylinder

is  . So if the top of the cylinder is submerged a distance

. So if the top of the cylinder is submerged a distance  below the surface of the liquid, the bottom of the cylinder is

a distance

below the surface of the liquid, the bottom of the cylinder is

a distance  below the surface of the liquid. Since the

sample of the liquid is at rest, the net force on the sample

must be zero by Newton's second law. So let's add up all the

forces on the sample and set the sum equal to 0. The pressure

on the bottom face of the cylinder is

below the surface of the liquid. Since the

sample of the liquid is at rest, the net force on the sample

must be zero by Newton's second law. So let's add up all the

forces on the sample and set the sum equal to 0. The pressure

on the bottom face of the cylinder is  . This is the pressure

from the liquid below the cylinder. The associated force

. This is the pressure

from the liquid below the cylinder. The associated force  is pushing

up. The liquid on top of the cylinder is pushing down.

The pressure is

is pushing

up. The liquid on top of the cylinder is pushing down.

The pressure is  and the associated force is

and the associated force is  .

The minus sign means the force is pointing down. There is also

gravity which applies a force of

.

The minus sign means the force is pointing down. There is also

gravity which applies a force of  where

where  is the mass

of the liquid in the cylinder. So we can write

is the mass

of the liquid in the cylinder. So we can write

|

(4) |

The density of the liquid is  . Density is the mass per unit

volume. So mass of the liquid sample is

. Density is the mass per unit

volume. So mass of the liquid sample is

where

where

is the volume of the cylinder. This means that

is the volume of the cylinder. This means that  .

Thus,

.

Thus,

|

(5) |

Cancelling the area  on each side of the equation gives:

on each side of the equation gives:

|

(6) |

This equation indicates that the pressure in a liquid depends only

on the depth  within the liquid. The pressure is therefore

the same at all points having the same depth, independent of the shape

of the container. Eq. (6) also indicates

that any increase in pressure at the surface must be transmitted

to every point in the liquid. This was first recognized by the French

scientist Blaise Pascal and is called Pascal's law: A change

in the pressure applied to an enclosed liquid is transmitted

undiminished to every point of the fluid and to the walls of the

container.

within the liquid. The pressure is therefore

the same at all points having the same depth, independent of the shape

of the container. Eq. (6) also indicates

that any increase in pressure at the surface must be transmitted

to every point in the liquid. This was first recognized by the French

scientist Blaise Pascal and is called Pascal's law: A change

in the pressure applied to an enclosed liquid is transmitted

undiminished to every point of the fluid and to the walls of the

container.

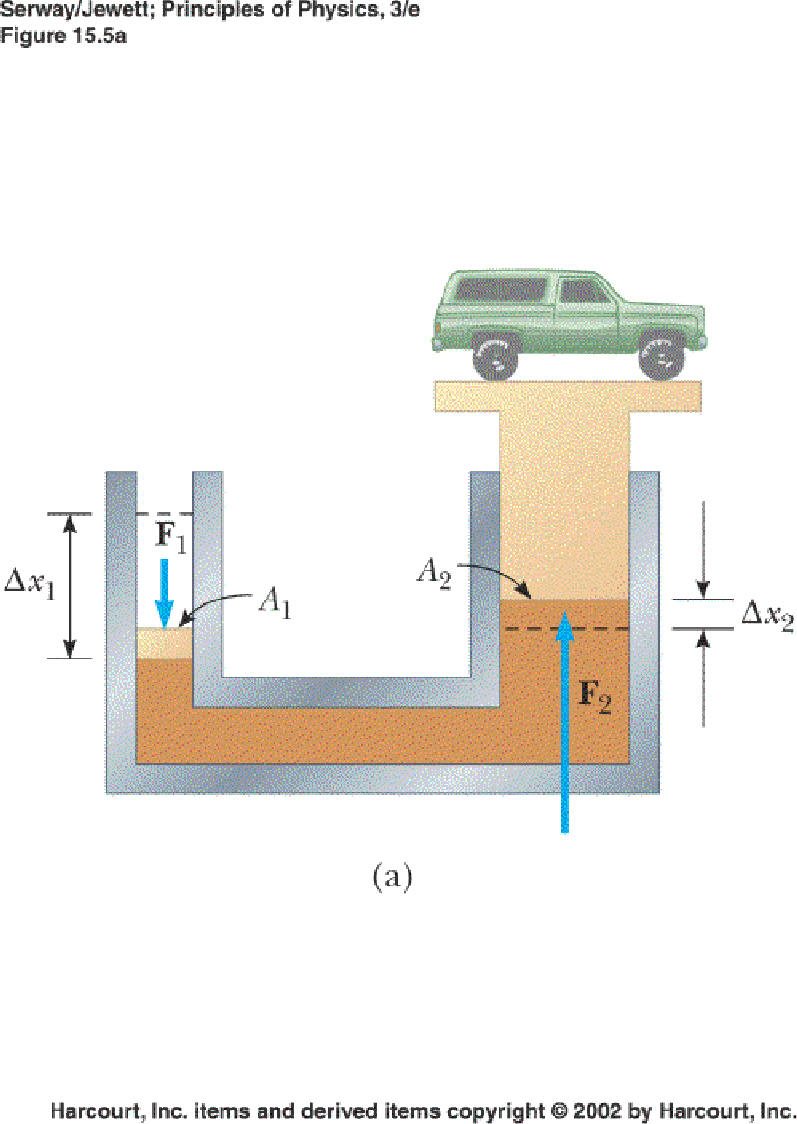

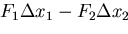

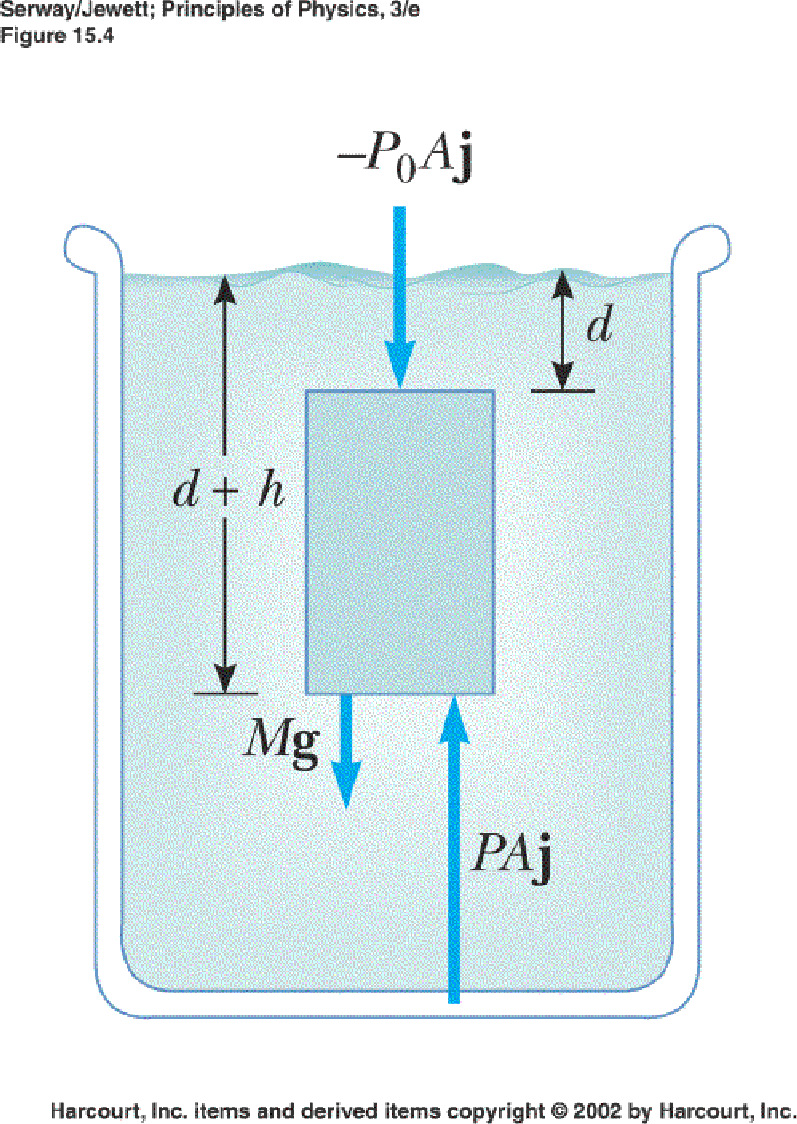

This explains how a hydraulic press works. A force  is applied to a small piston of cross sectional area

is applied to a small piston of cross sectional area  .

The pressure is transmitted through a liquid to a larger piston

of area

.

The pressure is transmitted through a liquid to a larger piston

of area  , and force

, and force  is exerted by the liquid

on the piston. Because the pressure is the same at both

pistons, we must have

is exerted by the liquid

on the piston. Because the pressure is the same at both

pistons, we must have

|

(7) |

or

|

(8) |

Thus  if

if  . The hydraulic lift amplifies

the force

. The hydraulic lift amplifies

the force  . Hydraulic brakes, car lifts, hydraulic

jacks, and forklifts all use this principle.

. Hydraulic brakes, car lifts, hydraulic

jacks, and forklifts all use this principle.

=3.0 true in

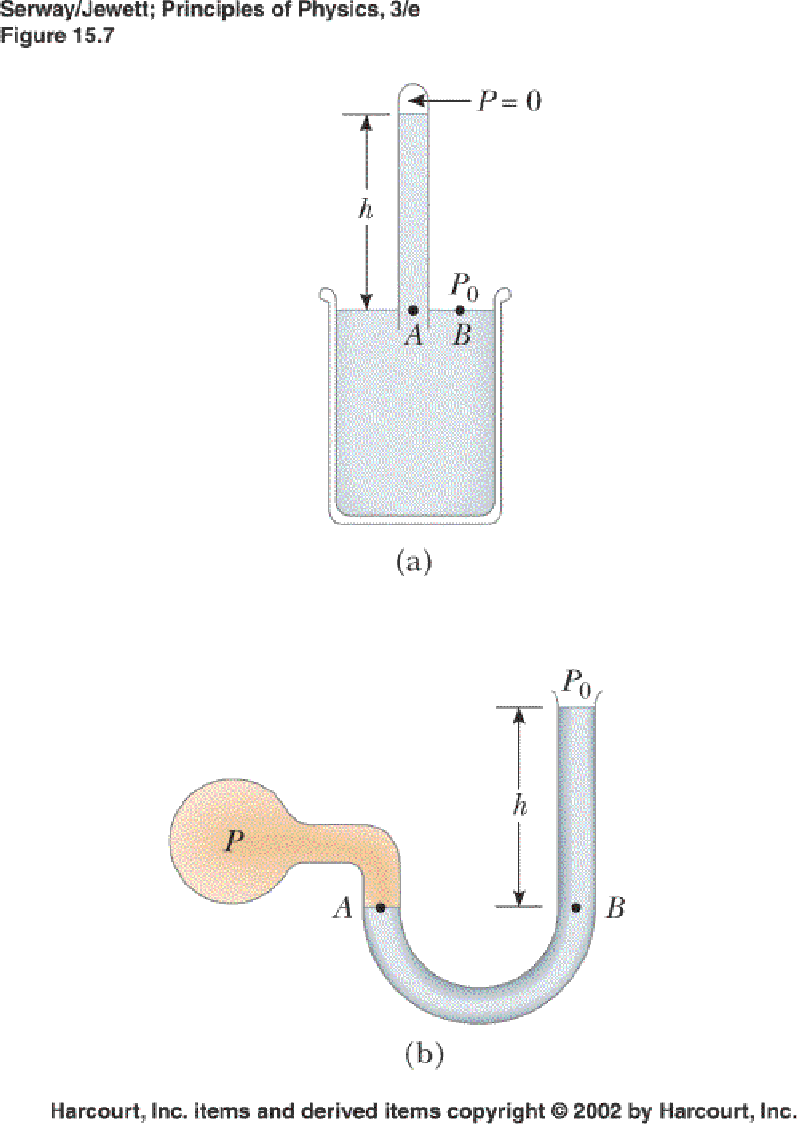

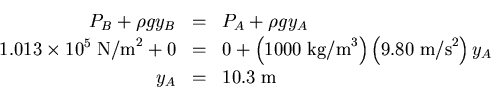

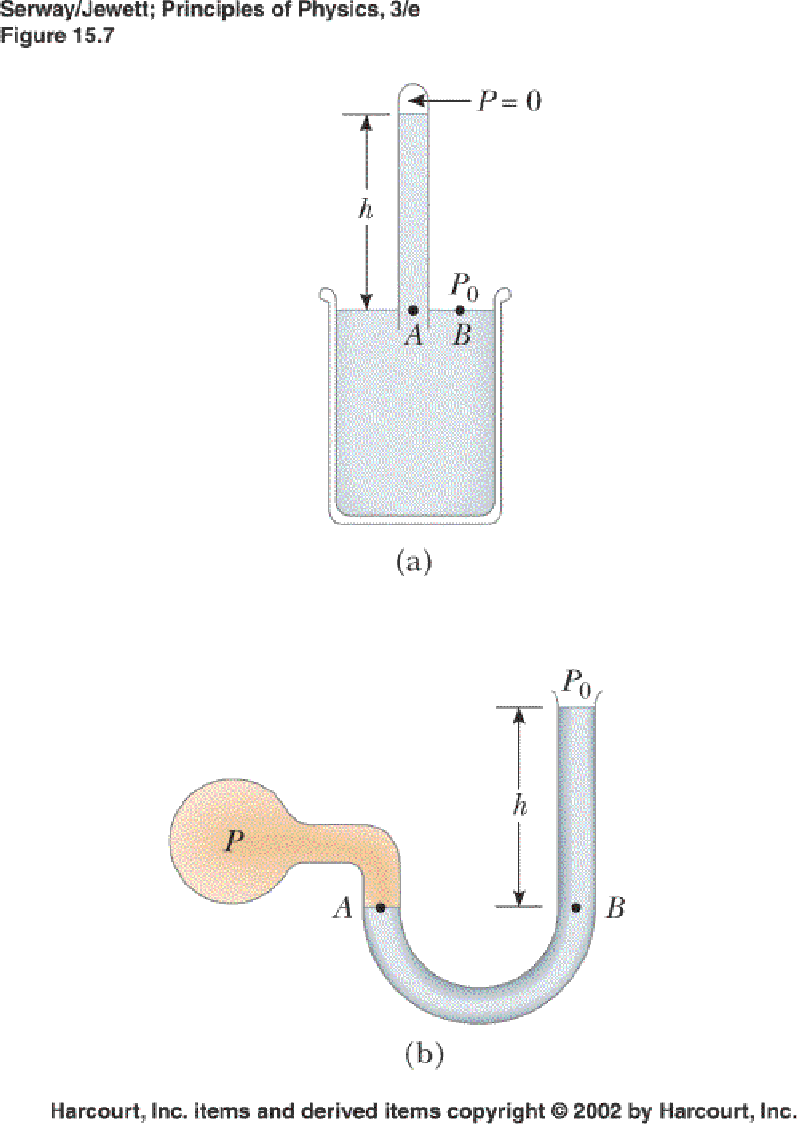

Pressure Measurements

Barometric pressure is often mentioned as part of weather

reports. This is the current pressure of the atmosphere which

varies a little from the standard pressure of 1 atm. A barometer

is used to measure the atmospheric pressure. It was invented by

Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647). A long tube closed at one end

is filled with mercury and then inverted into a dish of mercury.

The pressure at the closed end is basically zero since it's a vacuum

there. The pressure at point A at the mouth of the tube must be the

same as point B outside the tube on the surface of the mercury since

point A and point B are at the same height above the ground. If this

were not the case, mercury would move until the net force was zero.

So the atmospheric pressure must be given by

|

(9) |

or

|

(10) |

If  1 atm

1 atm

Pa,

Pa,  m

m  mm.

mm.

=3.0 true in

The open-tube manometer is a device for measuring the pressure

of a gas contained in a vessel. One end of the U-shaped tube

containing a liquid is open to the atmosphere, and the other end

is connected to a system of unknown pressure  . The pressures

at points A and B must be the same otherwise there would be a

net force and the liquid would accelerate. The pressure at A

is the unknown pressure

. The pressures

at points A and B must be the same otherwise there would be a

net force and the liquid would accelerate. The pressure at A

is the unknown pressure  of the gas. Equating the pressures

at A and B, we can write

of the gas. Equating the pressures

at A and B, we can write

|

(11) |

where  is the atmospheric pressure.

is the atmospheric pressure.  is called the

absolute pressure and

is called the

absolute pressure and  is called the gauge pressure.

The pressure you measure in a car tire is gauge pressure.

is called the gauge pressure.

The pressure you measure in a car tire is gauge pressure.

Example: Problem 15.12. Imagine Superman attempting

to drink water through a very long straw. With his great strength

he achieves maximum possible suction. The walls of the

tubular straw do not collapse. (a) Find the maximum height through

which he can lift the water. (b) Still thirsty, the Man of Steel

repeats his attempt on the Moon, which has no atmosphere. Find the difference

between the water levels inside and outside the straw.

Answer: Superman can produce a perfect vacuum in the straw. Take point

B at the water surface in the basin and point A at the water surface in the

straw. (see Figure 15.7 for location of points A and B)

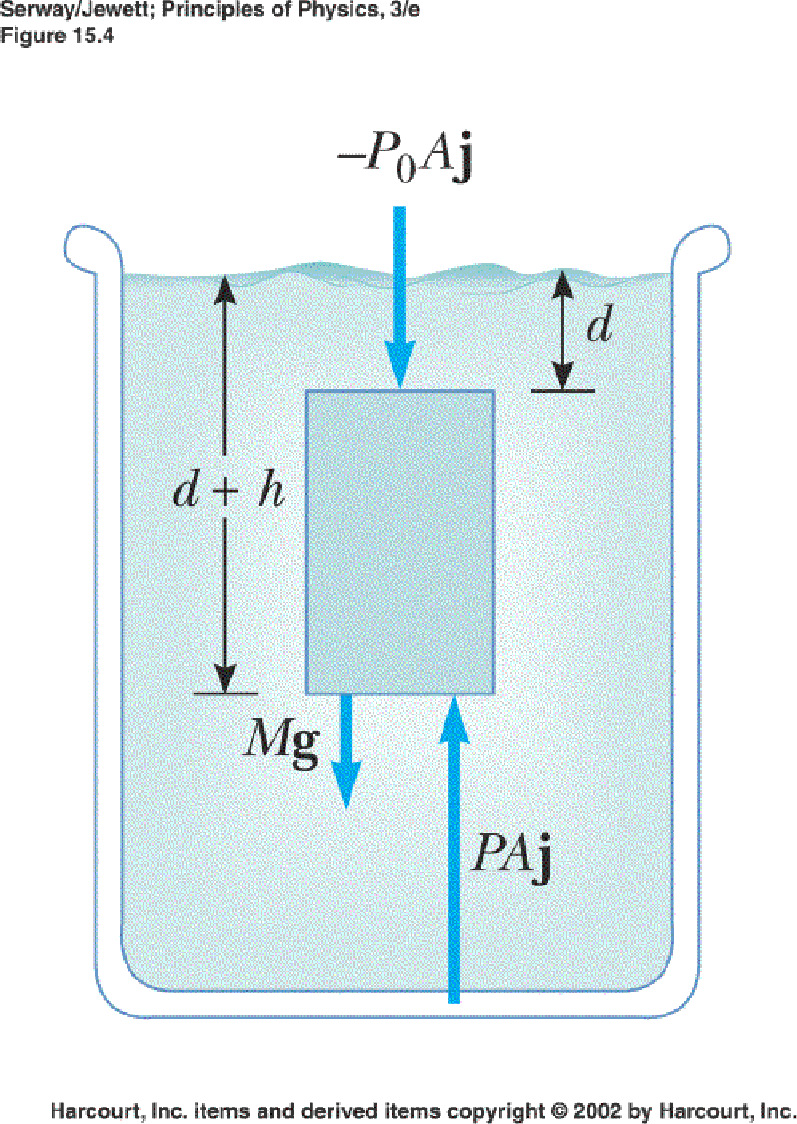

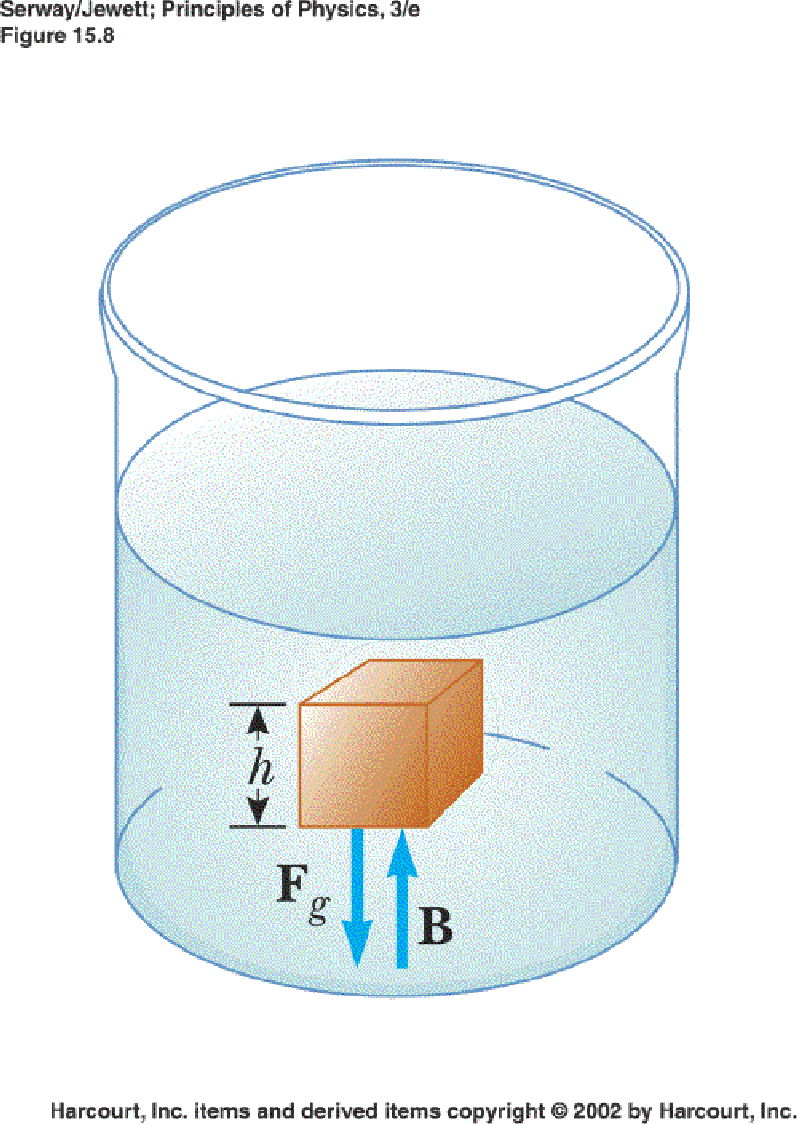

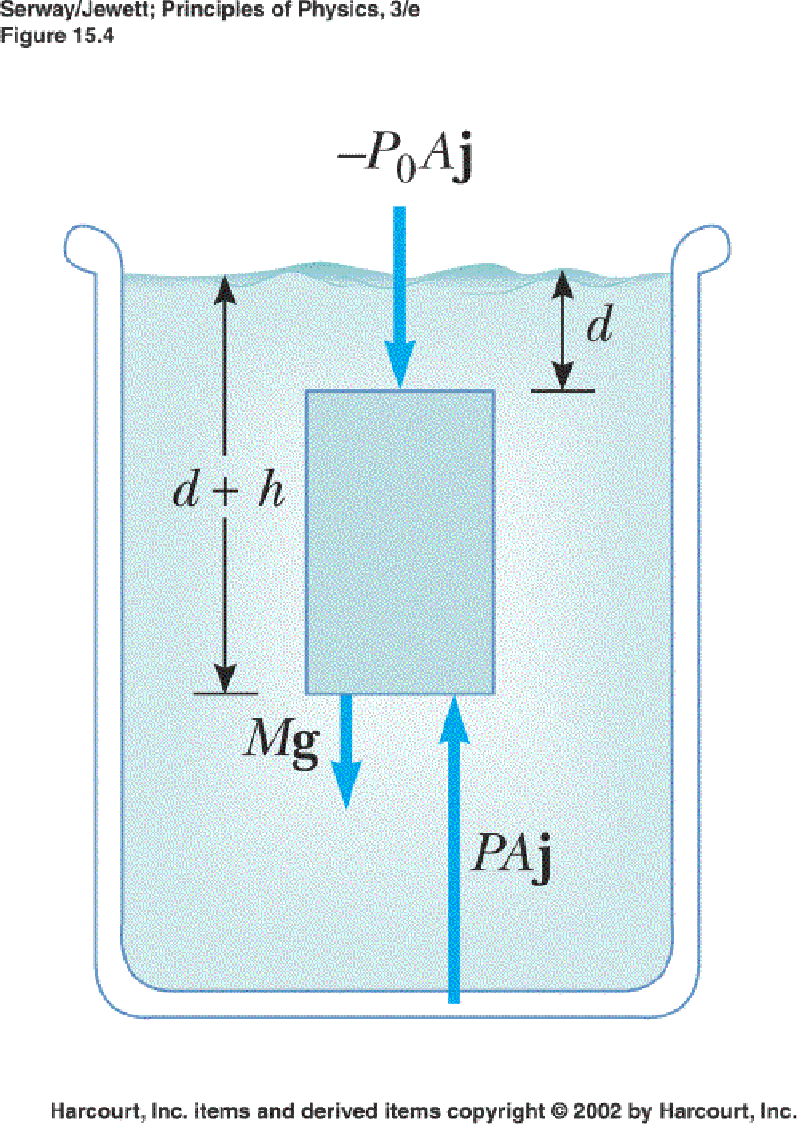

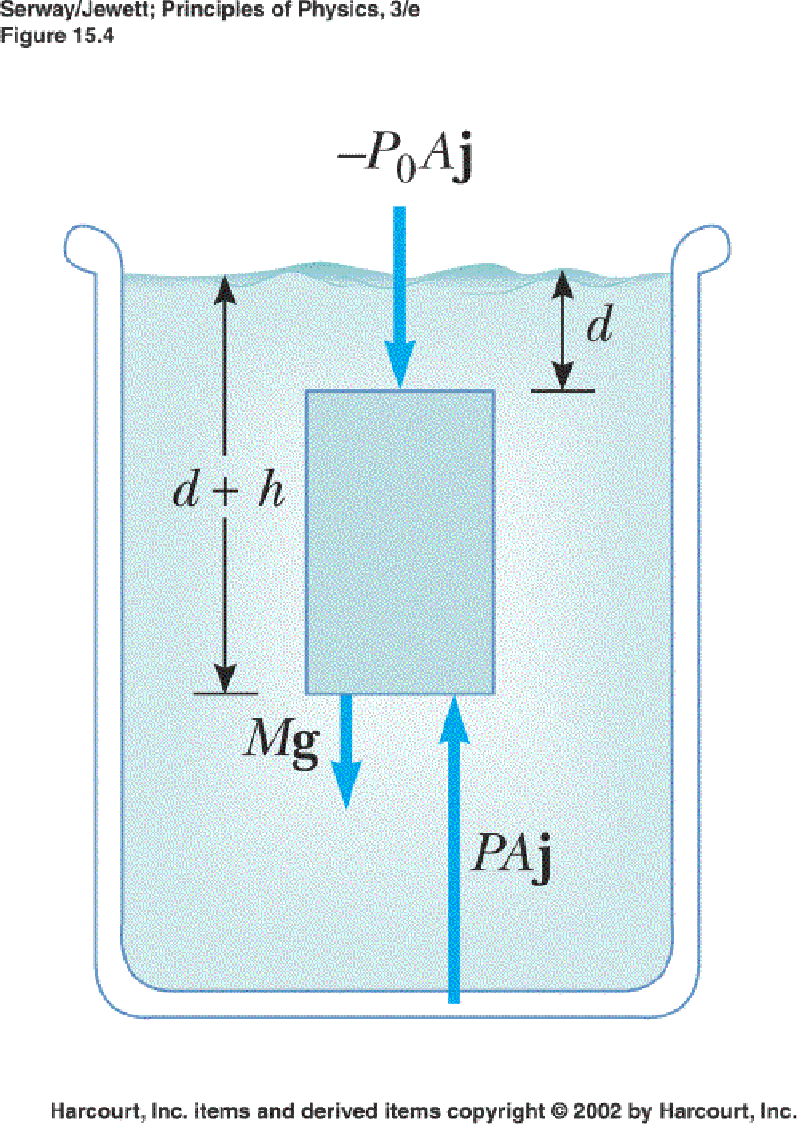

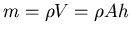

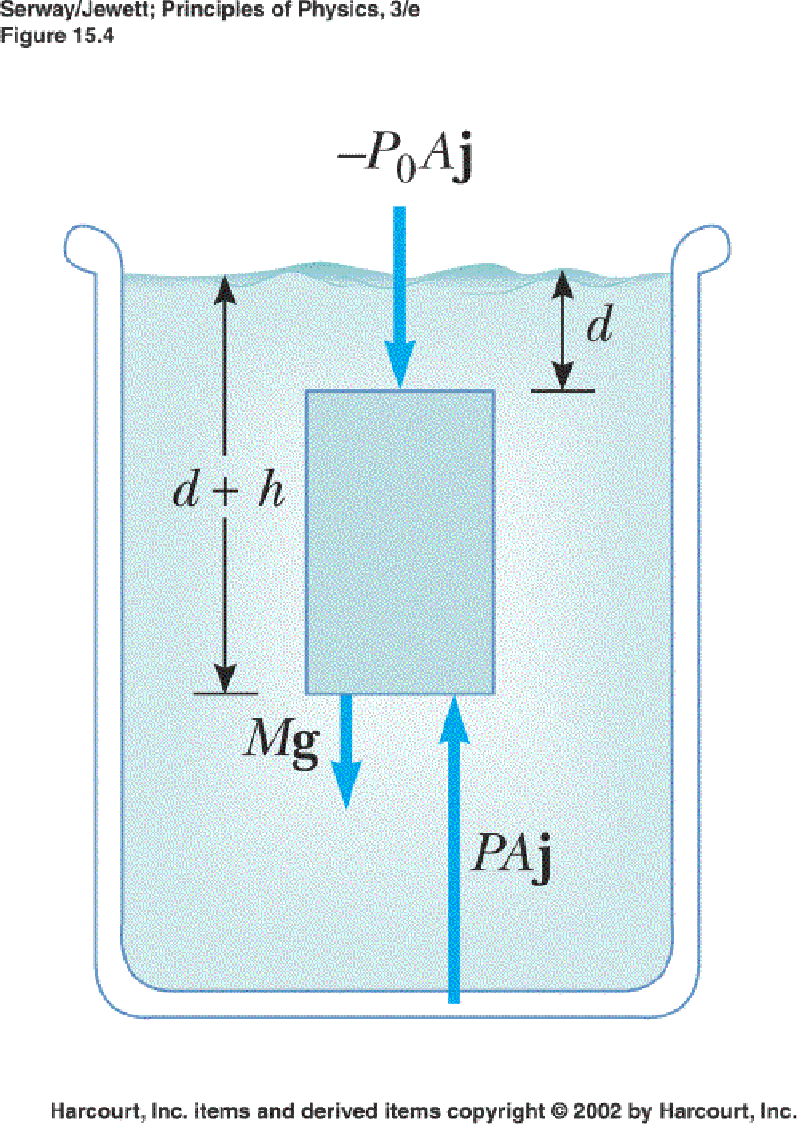

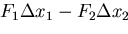

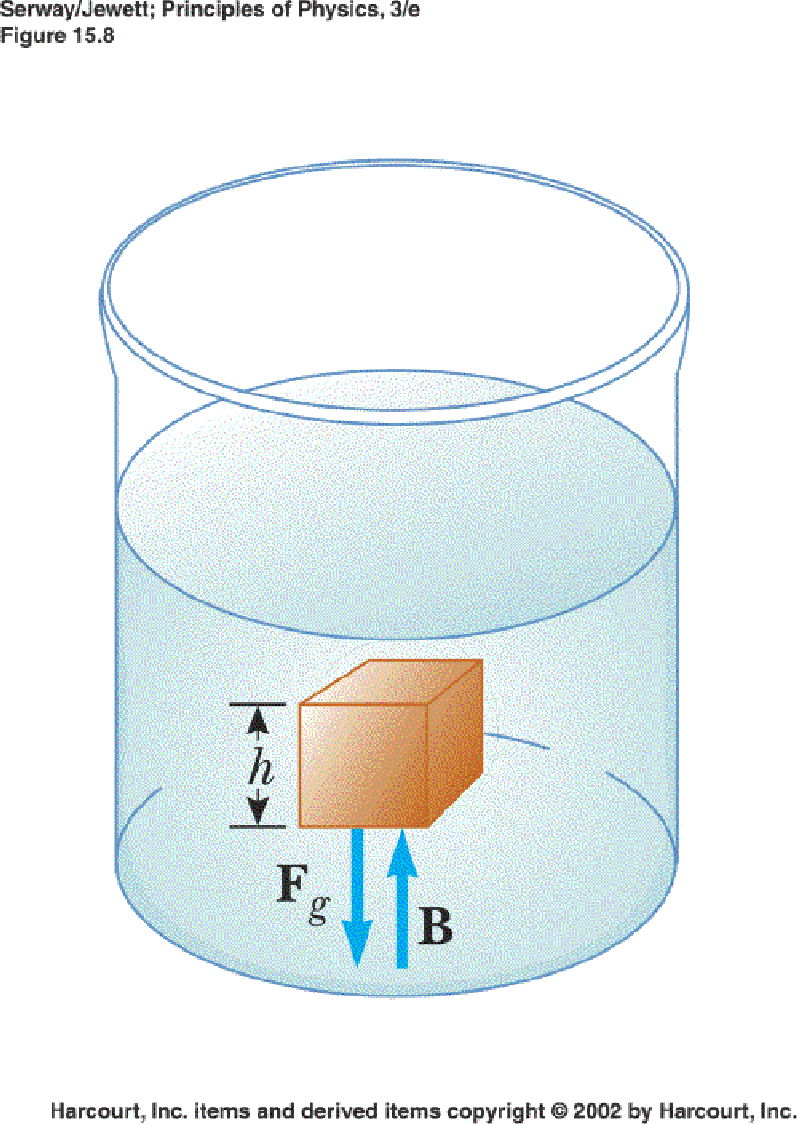

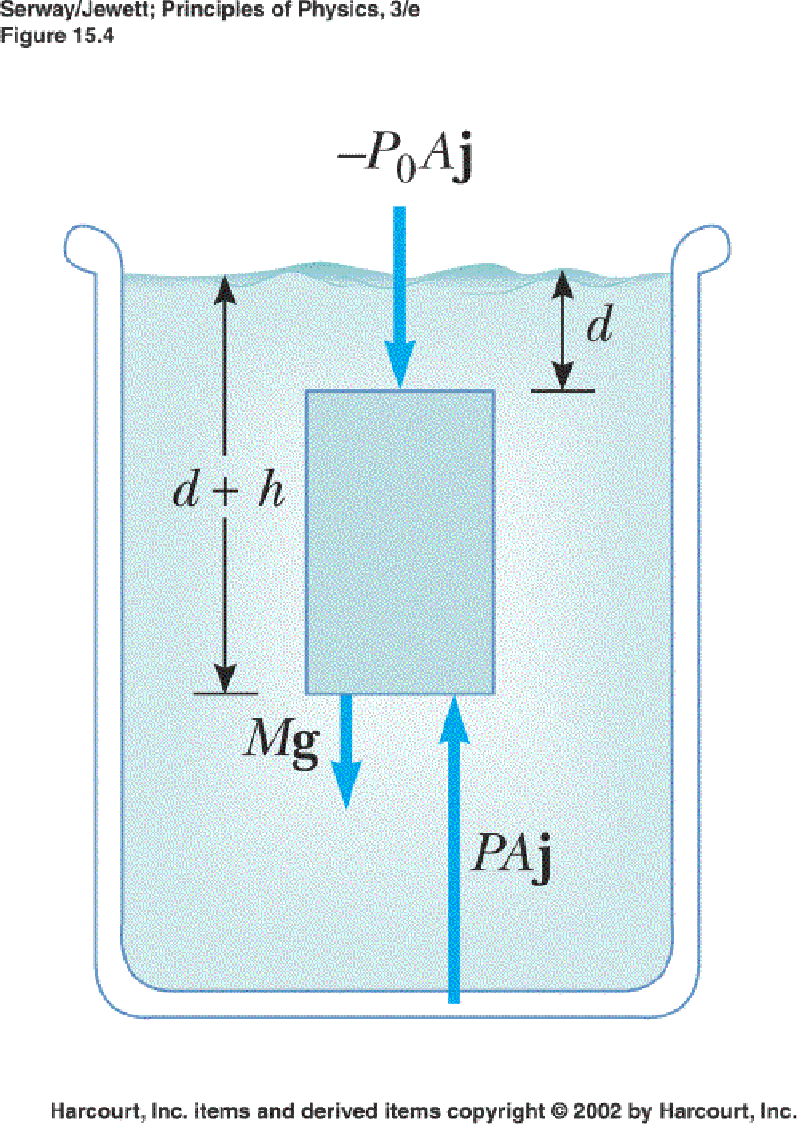

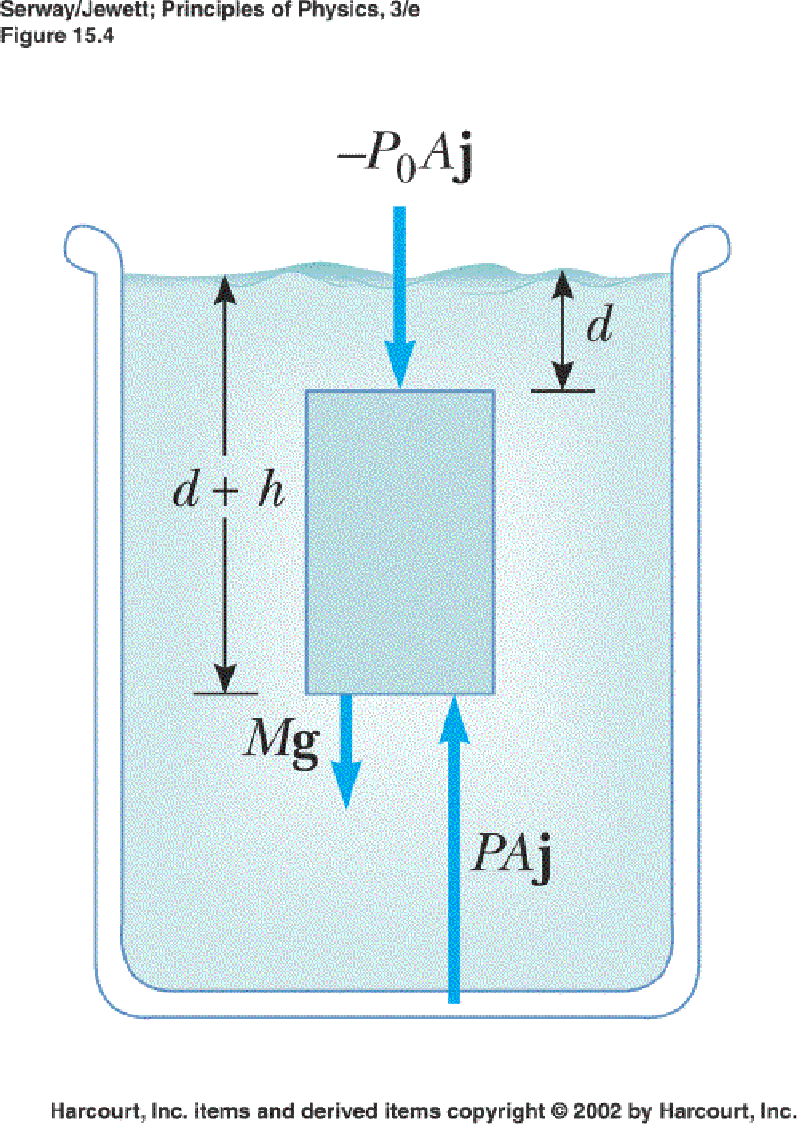

Buoyant Forces and Archimedes' Principle

Key Point: The force on an object is an upward force

produced by the liquid.

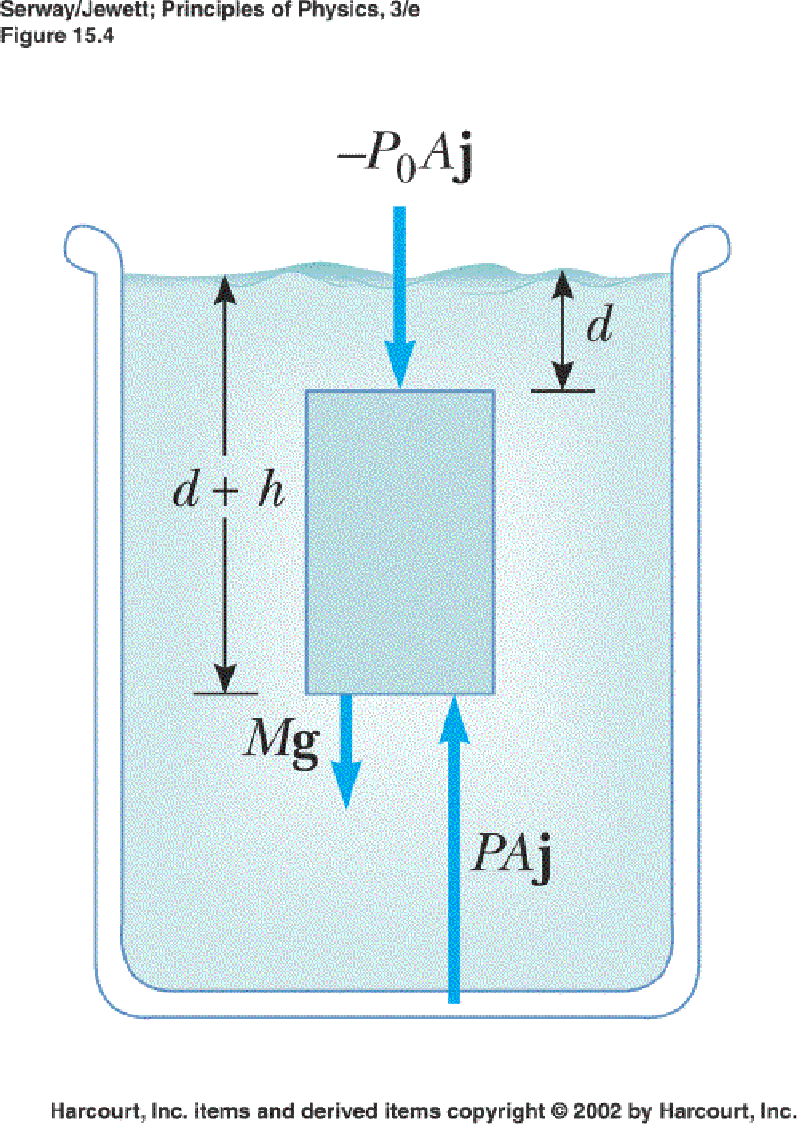

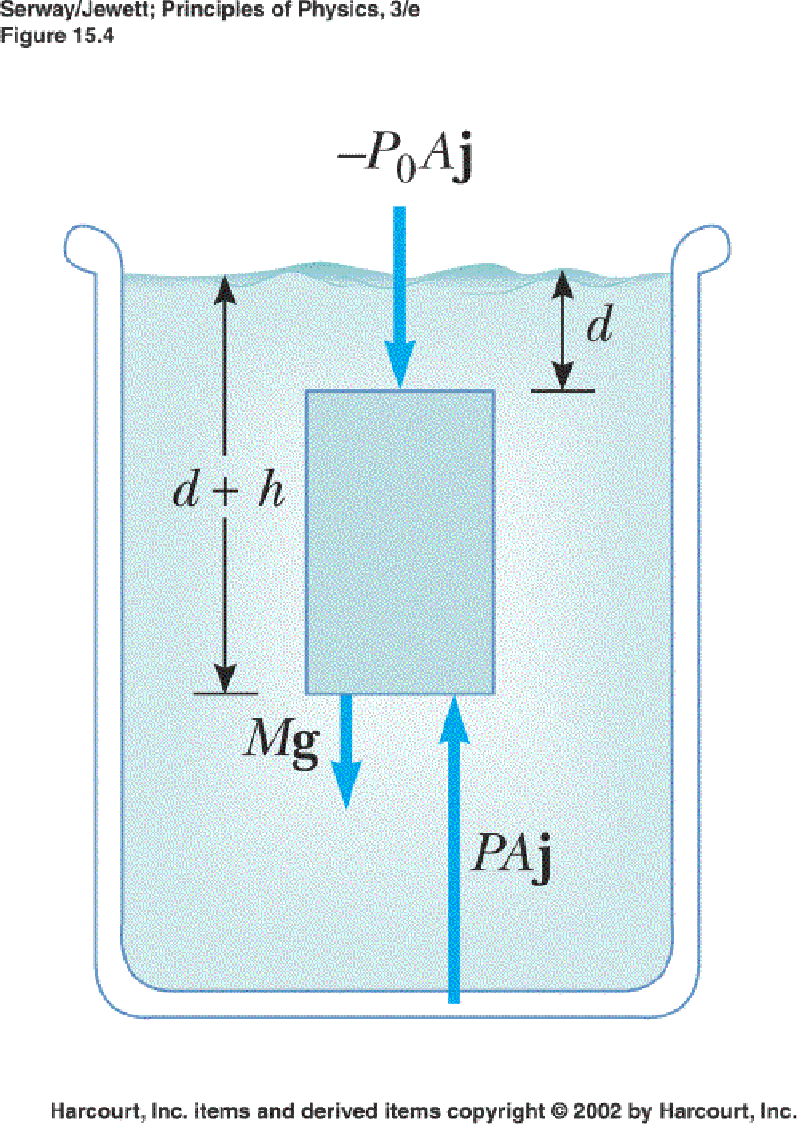

A buoyant force is an upward force exerted on an object by the

surrounding fluid. Buoyant forces are what keep ships and boats

afloat. They also are the reason it's easier to lift someone in

the water than on dry ground (JFK example).

Key Point: The buoyant force is equal to

the of the fluid displaced by the object.

The magnitude of

the buoyant force is given by Archimedes's principle: Any

object completely or partially submerged in a fluid experiences

an upward buoyant force whose magnitude is equal to the weight

of the fluid displaced by the object.

=3.0 true in

on the cube of fluid. Since it's

at rest, there must be an upward force cancelling gravity.

This upward force is the buoyant force

on the cube of fluid. Since it's

at rest, there must be an upward force cancelling gravity.

This upward force is the buoyant force  . Thus we can write

. Thus we can write

|

(12) |

If the density of the fluid is  , then

, then  ,

and we can write

,

and we can write

|

(13) |

where  is the volume of the cube.

Remember how we said that the pressure in a fluid varies with depth?

The buoyant force

is the volume of the cube.

Remember how we said that the pressure in a fluid varies with depth?

The buoyant force  is just the difference in the force between

the top and bottom of the cube:

is just the difference in the force between

the top and bottom of the cube:

|

(14) |

where the pressure  on the bottom of the cube is greater

than the pressure

on the bottom of the cube is greater

than the pressure  on the top.

on the top.

Now suppose we replace the cubic volume of fluid with a cube of

steel (same volume). The buoyant force on the steel is the same

as the buoyant force was on the cube of fluid with the same dimensions.

This is true for a submerged object of any shape, size, or density.

Suppose we have a submerged object with volume  and density

and density

. The force due to gravity is

. The force due to gravity is

.

The buoyant force is

.

The buoyant force is

. So the net force on

the object is

. So the net force on

the object is

|

(15) |

This equation implies that if the density of the object is less

than the density of the liquid, the net force will be positive,

so the object rises and will float.

If the density of the object is greater than the fluid, the net

force will be negative (downward) and the object will sink.

Now consider an object that floats on the surface of the fluid.

That means that it is only partially submerged. So the volume  of

displaced fluid is only a fraction of the total volume

of

displaced fluid is only a fraction of the total volume  of the object. Because the object is in equilibrium, the buoyant

force must balance gravity:

of the object. Because the object is in equilibrium, the buoyant

force must balance gravity:

Thus, the fraction of the volume of the object that is

submerged under the surface of the fluid is equal to the ratio

of the object density to the fluid density.

Fish are able to change the depths at which they swim by changing

the amount of gas in its swim bladder which is a gas-filled cavity

inside the fish. Increasing the size of the bladder increases

the amount of water displaced and hence the buoyant force. So the fish

rises. Decreasing the size of the bladder allows the fish to sink

deeper.

A ship floats because the buoyant force balances the weight of the

ship. If the ship takes on extra cargo, it rides lower in the water

because the extra volume of displaced water means the buoyant force

is increased to compensate for the increased weight.

Fluid Dynamics

So far we've considered fluids at rest. Now let's turn our attention

to fluid dynamics, i.e., fluids in motion. There are 2 ways in which

fluids can flow. The first way is steady, smooth flow that is called

laminar flow. Each bit of fluid follows a smooth path so that

different paths never cross each other. We can imagine a ``velocity

field'' in which each point in the fluid is associated with a vector

that corresponds to the velocity of the fluid at that point. For

laminar flow, the velocity of the fluid at each point remains constant

in time. In other words, the velocity field is does not change with

time. The other type of flow is turbulent flow. Turbulent flow is

irregular and has whirlpools. Think of white water rapids.

Viscosity is often used to characterize the ease of flow.

Honey is very viscous. Highly viscous fluids resist flow and do

not flow easily, e.g., ketchup. There is a sort of internal friction

as parts of the fluid try to flow or move past other parts.

Fluids can be very complicated. To make things simpler, we make the

following 4 assumptions about the fluids we will consider:

- Nonviscous fluid which has no resistance to flow.

- Incompressible fluid in which the density of the fluid is

assumed to remain constant regardless of the pressure in the fluid.

- Steady flow where the velocity field remains constant

in time.

- Irrotational flow which means the fluid about any point

has no angular angular momentum. So a small paddle wheel placed anywhere

in the fluid does not rotate.

The first 2 assumptions are properties of our ideal fluid. The last 2

describe the way the fluid flows.

Streamlines and the continuity equation for fluids

The path taken by a particle during steady flow is called a streamline.

The velocity of the particle is tangent to the streamline.

Streamlines cannot cross because if they did, a particle would have a

choice of paths and would sometimes take one path and sometimes the other

path. Then the flow wouldn't be steady. A set of streamlines forms a

tube of flow. It's like a pipe with invisible walls.

=3.0 true in

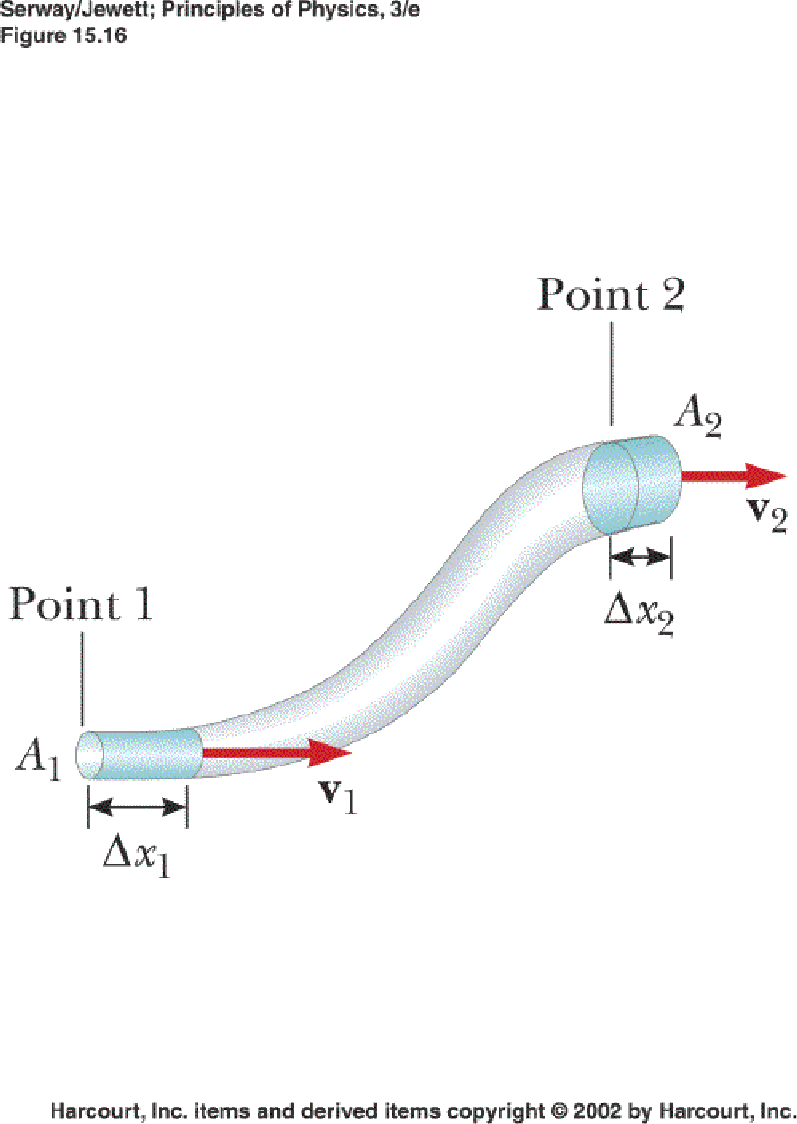

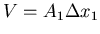

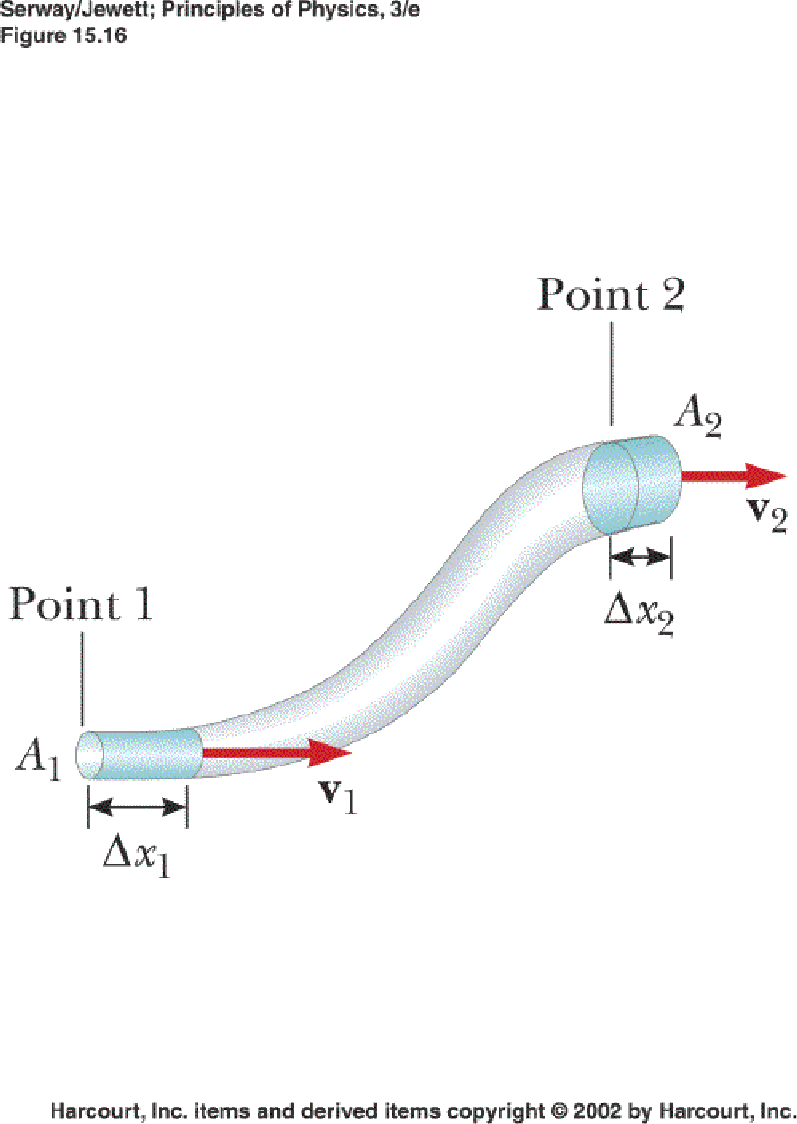

Consider fluid flowing in a pipe which is wider at the exit than at

the entrance. Steady flow means that the amount or volume of fluid

entering a pipe in a time interval  must equal the volume

leaving it in this time interval

must equal the volume

leaving it in this time interval  .

Let the cross-sectional area at the entrance be

.

Let the cross-sectional area at the entrance be  and let the cross-sectional area at the exit be

and let the cross-sectional area at the exit be  . Suppose

that in a time interval

. Suppose

that in a time interval  , a volume

, a volume  of fluid enters

the pipe. Since the cross-sectional area at the entrance is

of fluid enters

the pipe. Since the cross-sectional area at the entrance is

, the length of the fluid segment must be

, the length of the fluid segment must be  such

that

such

that

. Since the fluid is incompressible, this

same volume of fluid must exit the pipe. The volume of the

exiting fluid is

. Since the fluid is incompressible, this

same volume of fluid must exit the pipe. The volume of the

exiting fluid is

where

where  is the

length of the segment of departing fluid. Thus we can write

is the

length of the segment of departing fluid. Thus we can write

|

(17) |

If we divide this equation by the time interval  , we have

, we have

|

(18) |

In the limit that

,

,

and we can write

and we can write

|

(19) |

This equation is called the continuity equation for fluids. It

says that the product of the cross-sectional area of the fluid

and the fluid speed is a constant at all points along the pipe.

So if  decreases, then

decreases, then  must increase.

must increase.

Key Point: Fluid flows in a narrower pipe.

This is why water squirts out faster from a nozzle or when you put your thumb

across part of the opening of a hose. You decrease the area

by constricting the opening and so the water speeds up.

The product  has the dimensions of volume per time and is

called the volume flow rate.

has the dimensions of volume per time and is

called the volume flow rate.

Bernoulli's Principle

You may have noticed that when you take a shower, the shower curtain

moves inwards toward you. This is because when water and air flow

past the shower curtain, they produce less pressure on the curtain

than when the air is still as it is on the outside of the curtain.

Since the pressure is greater outside than inside the shower,

the curtain moves inward.

=3.0 true in

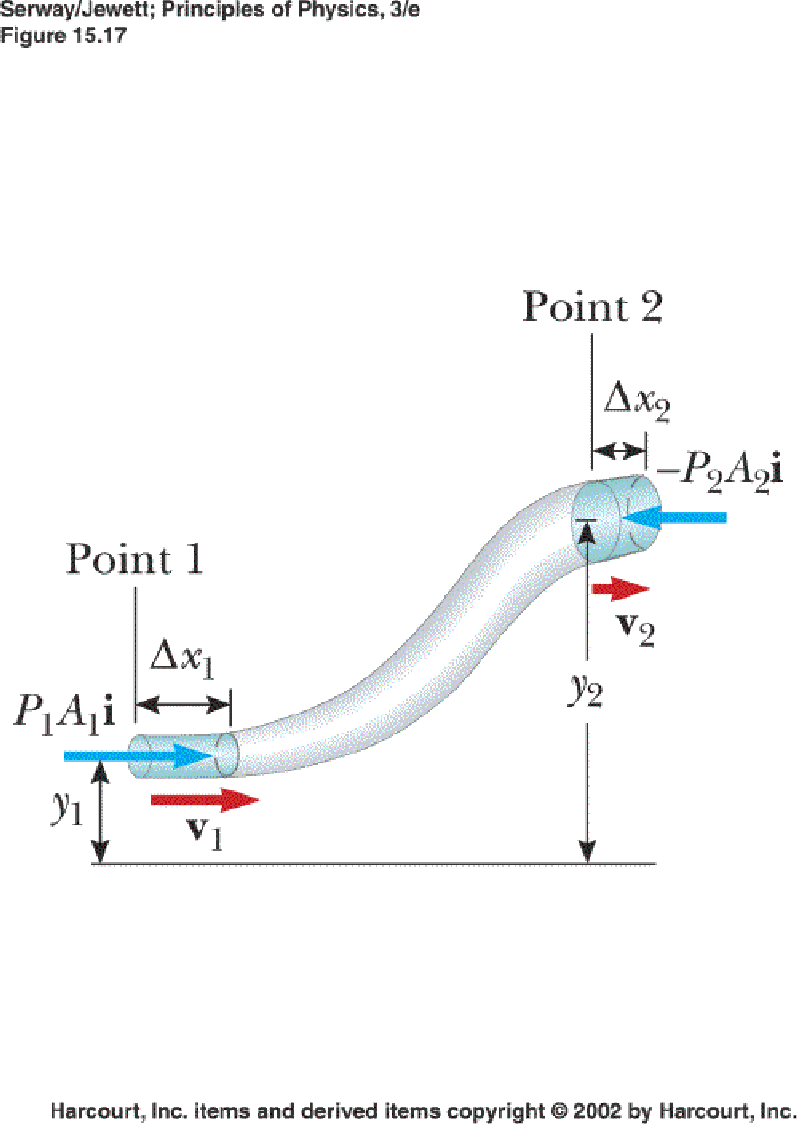

This is an example of Bernoulli's principle which explicitly shows

the dependence of pressure on speed and elevation. Consider a section

of fluid between point 1 and 2 in a pipe through which fluid is flowing.

At the beginning of the time interval  , the section is

between point 1 and point 2. At the end of the time interval, the

section has moved to be between (point 1 +

, the section is

between point 1 and point 2. At the end of the time interval, the

section has moved to be between (point 1 +  ) and

(point 2 +

) and

(point 2 +  ).

Suppose the pipe changes

elevation and that its diameter changes so that it has

cross-sectional area

).

Suppose the pipe changes

elevation and that its diameter changes so that it has

cross-sectional area  at the left end and cross-sectional

area

at the left end and cross-sectional

area  at the right end of the section we are considering.

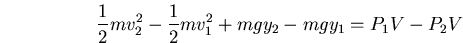

Energy is conserved so we can write

at the right end of the section we are considering.

Energy is conserved so we can write

|

(20) |

Since the cross-sectional area is different between points 1 and 2,

the velocities and hence the kinetic energies are different. So

|

(21) |

Here  is the mass of fluid in a little chunk of volume

is the mass of fluid in a little chunk of volume

. The chunk at point 1 and point 2

have the same volume and the same mass because the fluid is

incompressible.

. The chunk at point 1 and point 2

have the same volume and the same mass because the fluid is

incompressible.

The change in elevation means that the gravitational potential

energy changes:

|

(22) |

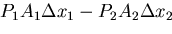

Finally we evaluate the work done on the section of fluid. The fluid

to the left of our section is pushing on our section and so is doing

work  on it. The fluid to the right is pushing against

the flow and so the displacement is opposite to the direction of

the force which gives negative work

on it. The fluid to the right is pushing against

the flow and so the displacement is opposite to the direction of

the force which gives negative work

. The net work

done on the system is

. The net work

done on the system is

Plugging into Eq. 20, we get

|

(24) |

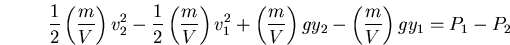

Dividing both sides by  gives

gives

|

(25) |

Using  , we obtain

, we obtain

|

(26) |

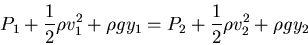

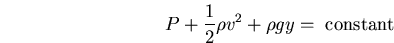

This is Bernoulli's equation. It is often expressed as

|

(27) |

Bernoulli's equation says that the sum of the pressure  , the kinetic

energy per unit volume

, the kinetic

energy per unit volume

, and the gravitational

potential energy per unit volume

, and the gravitational

potential energy per unit volume  has the same value at

all points along a streamline. This means that if one terms

increases, the other terms must decrease to compensate and keep

the sum of terms constant.

has the same value at

all points along a streamline. This means that if one terms

increases, the other terms must decrease to compensate and keep

the sum of terms constant.

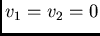

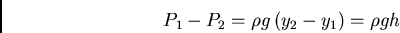

When the fluid is at rest,

and Bernoulli's equation becomes

and Bernoulli's equation becomes

|

(28) |

which agrees with Eq. (6). Notice that if there

is no change in height, then

|

(29) |

So a velocity difference means there is a pressure difference.

Key Point: Moving fluids exert pressure than

stationary fluids.

If  ,

,  . This explains the shower curtain.

The air and water are moving faster inside the shower than outside,

so the presure is less inside the shower curtain and the curtain

moves inward.

. This explains the shower curtain.

The air and water are moving faster inside the shower than outside,

so the presure is less inside the shower curtain and the curtain

moves inward.

Some other applications of fluid dynamics

=3.0 true in

There is also an upward force due to the air deflected downward by

the wing. According to Newton's third law, the wing applies a force

on the air to deflect it downward and so the air applies an equal

and opposite force to push the wing upward.

These two forces taken together tend to lift the wing

against gravity and are therefore known as LIFT.

=3.0 true in

Another application is atomizers and paint sprayers. A stream

of air passing over an open tube reduces the pressure above the

tube. This reduction in pressure causes the liquid to rise into

the air stream. The liquid is then dispersed into a fine spray of

droplets.

Bernoulli's principle also explains vascular flutter. In advanced

arteriosclerosis, plaque accumulates on the wall of a blood vessel

and constricts the opening where the blood flows. As a result,

the blood flows faster which in turn reduces the pressure on the

inside of the blood vessel. The external pressure can cause the

walls of the blood vessel to collapse, blocking the flow of blood.

Since the blood momentarily stops flowing, the pressure inside

the blood vessel rises, the walls are restored and the vessel

reopens restoring blood flow. Then the cycle repeats itself.

Such variations in blood flow can be heard with a stethoscope.

=3.0 true in

One final example is the ``bar room bet.'' Take a cocktail napkin or fold a piece of

paper. Put it on the table like a little tent. What is the best way to blow on

it to get it to flatten onto the table? Bet someone that you can flatten it

better than they can by just blowing on it.

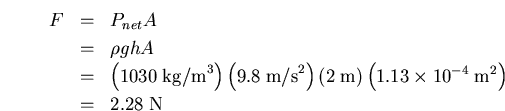

Example: Problem 15.38 A legendary Dutch boy saved Holland by plugging

a hole in a dike with his finger, 1.20 cm in diameter. If the hole was 2.00 m

below the surface of the North Sea (density 1030 kg/m ), (a) what was

the force on his finger? (b) If he pulled his finger out of the hole, during

what time interval would the released water fill 1 acre of land to a depth

of 1 ft? Assume that the hole remained constant in size. (A typical U.S.

family of four uses 1 acre-foot of water, 1234 m

), (a) what was

the force on his finger? (b) If he pulled his finger out of the hole, during

what time interval would the released water fill 1 acre of land to a depth

of 1 ft? Assume that the hole remained constant in size. (A typical U.S.

family of four uses 1 acre-foot of water, 1234 m , in 1 year.)

, in 1 year.)

Solution: (a) The force  where

where  is the pressure

on his finger and

is the pressure

on his finger and  is the area of the

hole. The radius

is the area of the

hole. The radius  where the diameter

where the diameter  cm = 0.012 m. So the

area of the hole is

cm = 0.012 m. So the

area of the hole is

|

(30) |

We need the net pressure on his finger, so we calculate the pressure from

the sea and the pressure from the air around his hand. The pressure on his

hand from the air is  1 atm =

1 atm =

Pa =

Pa =

N/m

N/m . The sea pressure

. The sea pressure

. So the

net pressure on his finger is

. So the

net pressure on his finger is

. Therefore the net force

on his finger is

. Therefore the net force

on his finger is

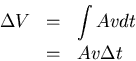

(b) To find the time to fill a volume  = 1234 m

= 1234 m , we need the volume

rate of flow

, we need the volume

rate of flow  where

where  is time. We note that

is time. We note that

|

(31) |

where the area  is the area of the hole out of which the water flows and

is the area of the hole out of which the water flows and

is the velocity of the water coming out of the hole. You can check this

relation by seeing if the units are the same on each side of the equation.

We can integrate this equation to get the volume in terms of the time:

is the velocity of the water coming out of the hole. You can check this

relation by seeing if the units are the same on each side of the equation.

We can integrate this equation to get the volume in terms of the time:

Alternatively, since  is independent of time, we can rewrite Eq. (31)

to get

is independent of time, we can rewrite Eq. (31)

to get

|

(32) |

where  1234 m

1234 m and

and  is the time needed to fill that volume.

Solving for

is the time needed to fill that volume.

Solving for  gives

gives

|

(33) |

We have the volume  and the area

and the area  .

To find the velocity

.

To find the velocity  , we use Bernoulli's equation:

, we use Bernoulli's equation:

|

(34) |

Let the left side represent the sea side of the hole and the right side represent

the air side of the hole. The velocity of the sea  on the sea side

of the hole. We can set

on the sea side

of the hole. We can set  (assume the hole is on the ground or is where we measure height from).

We also have

(assume the hole is on the ground or is where we measure height from).

We also have  = 1 atm. So we have

= 1 atm. So we have

Plugging into Eq. (33), we get

Next: About this document ...

Clare Yu

2008-01-03

at rest.

Consider a portion of the liquid contained within an imaginary

cylinder of cross-sectional area

at rest.

Consider a portion of the liquid contained within an imaginary

cylinder of cross-sectional area ![]() . The height of the cylinder

is

. The height of the cylinder

is ![]() . So if the top of the cylinder is submerged a distance

. So if the top of the cylinder is submerged a distance ![]() below the surface of the liquid, the bottom of the cylinder is

a distance

below the surface of the liquid, the bottom of the cylinder is

a distance ![]() below the surface of the liquid. Since the

sample of the liquid is at rest, the net force on the sample

must be zero by Newton's second law. So let's add up all the

forces on the sample and set the sum equal to 0. The pressure

on the bottom face of the cylinder is

below the surface of the liquid. Since the

sample of the liquid is at rest, the net force on the sample

must be zero by Newton's second law. So let's add up all the

forces on the sample and set the sum equal to 0. The pressure

on the bottom face of the cylinder is ![]() . This is the pressure

from the liquid below the cylinder. The associated force

. This is the pressure

from the liquid below the cylinder. The associated force ![]() is pushing

up. The liquid on top of the cylinder is pushing down.

The pressure is

is pushing

up. The liquid on top of the cylinder is pushing down.

The pressure is ![]() and the associated force is

and the associated force is ![]() .

The minus sign means the force is pointing down. There is also

gravity which applies a force of

.

The minus sign means the force is pointing down. There is also

gravity which applies a force of ![]() where

where ![]() is the mass

of the liquid in the cylinder. So we can write

is the mass

of the liquid in the cylinder. So we can write

. Density is the mass per unit

volume. So mass of the liquid sample is

. Density is the mass per unit

volume. So mass of the liquid sample is

![]() is applied to a small piston of cross sectional area

is applied to a small piston of cross sectional area ![]() .

The pressure is transmitted through a liquid to a larger piston

of area

.

The pressure is transmitted through a liquid to a larger piston

of area ![]() , and force

, and force ![]() is exerted by the liquid

on the piston. Because the pressure is the same at both

pistons, we must have

is exerted by the liquid

on the piston. Because the pressure is the same at both

pistons, we must have

Pa,

Pa, ![]() . The pressures

at points A and B must be the same otherwise there would be a

net force and the liquid would accelerate. The pressure at A

is the unknown pressure

. The pressures

at points A and B must be the same otherwise there would be a

net force and the liquid would accelerate. The pressure at A

is the unknown pressure ![]() of the gas. Equating the pressures

at A and B, we can write

of the gas. Equating the pressures

at A and B, we can write

, then

, then  ,

and we can write

,

and we can write

![]() and density

and density

![]() . The force due to gravity is

. The force due to gravity is

![]() .

The buoyant force is

.

The buoyant force is

![]() . So the net force on

the object is

. So the net force on

the object is

![]() of

displaced fluid is only a fraction of the total volume

of

displaced fluid is only a fraction of the total volume ![]() of the object. Because the object is in equilibrium, the buoyant

force must balance gravity:

of the object. Because the object is in equilibrium, the buoyant

force must balance gravity:

![]() must equal the volume

leaving it in this time interval

must equal the volume

leaving it in this time interval ![]() .

Let the cross-sectional area at the entrance be

.

Let the cross-sectional area at the entrance be ![]() and let the cross-sectional area at the exit be

and let the cross-sectional area at the exit be ![]() . Suppose

that in a time interval

. Suppose

that in a time interval ![]() , a volume

, a volume ![]() of fluid enters

the pipe. Since the cross-sectional area at the entrance is

of fluid enters

the pipe. Since the cross-sectional area at the entrance is

![]() , the length of the fluid segment must be

, the length of the fluid segment must be ![]() such

that

such

that

![]() . Since the fluid is incompressible, this

same volume of fluid must exit the pipe. The volume of the

exiting fluid is

. Since the fluid is incompressible, this

same volume of fluid must exit the pipe. The volume of the

exiting fluid is

where

where ![]() is the

length of the segment of departing fluid. Thus we can write

is the

length of the segment of departing fluid. Thus we can write

![]() has the dimensions of volume per time and is

called the volume flow rate.

has the dimensions of volume per time and is

called the volume flow rate.

![]() , the section is

between point 1 and point 2. At the end of the time interval, the

section has moved to be between (point 1 +

, the section is

between point 1 and point 2. At the end of the time interval, the

section has moved to be between (point 1 + ![]() ) and

(point 2 +

) and

(point 2 + ![]() ).

Suppose the pipe changes

elevation and that its diameter changes so that it has

cross-sectional area

).

Suppose the pipe changes

elevation and that its diameter changes so that it has

cross-sectional area ![]() at the left end and cross-sectional

area

at the left end and cross-sectional

area ![]() at the right end of the section we are considering.

Energy is conserved so we can write

at the right end of the section we are considering.

Energy is conserved so we can write

. The net work

done on the system is

. The net work

done on the system is

![]() and Bernoulli's equation becomes

and Bernoulli's equation becomes

![]() ,

, ![]() . This explains the shower curtain.

The air and water are moving faster inside the shower than outside,

so the presure is less inside the shower curtain and the curtain

moves inward.

. This explains the shower curtain.

The air and water are moving faster inside the shower than outside,

so the presure is less inside the shower curtain and the curtain

moves inward.

), (a) what was

the force on his finger? (b) If he pulled his finger out of the hole, during

what time interval would the released water fill 1 acre of land to a depth

of 1 ft? Assume that the hole remained constant in size. (A typical U.S.

family of four uses 1 acre-foot of water, 1234 m

), (a) what was

the force on his finger? (b) If he pulled his finger out of the hole, during

what time interval would the released water fill 1 acre of land to a depth

of 1 ft? Assume that the hole remained constant in size. (A typical U.S.

family of four uses 1 acre-foot of water, 1234 m , in 1 year.)

, in 1 year.)

![]() where

where ![]() is the pressure

on his finger and

is the pressure

on his finger and ![]() is the area of the

hole. The radius

is the area of the

hole. The radius ![]() where the diameter

where the diameter ![]() cm = 0.012 m. So the

area of the hole is

cm = 0.012 m. So the

area of the hole is

![]() = 1234 m

= 1234 m , we need the volume

rate of flow

, we need the volume

rate of flow  where

where ![]() is time. We note that

is time. We note that

and

and ![]() and the area

and the area ![]() .

To find the velocity

.

To find the velocity ![]() , we use Bernoulli's equation:

, we use Bernoulli's equation: