Next: About this document ...

LECTURE 7

General Relations for a Homogeneous Substance

For simplicity we will omit the averaging bar; macroscopic quantities

such as energy  and pressure

and pressure  will be understood to refer to their

mean values. A macrostate can be specified by 2 macroscopic variables.

For example if we specify the volume

will be understood to refer to their

mean values. A macrostate can be specified by 2 macroscopic variables.

For example if we specify the volume  and internal energy

and internal energy  , then

the other macroscopic parameters such as

, then

the other macroscopic parameters such as  and

and  are then determined.

We usually like to specify the macroscopic parameters which we can

control in the lab or in our simulation. So

are then determined.

We usually like to specify the macroscopic parameters which we can

control in the lab or in our simulation. So  and

and  may not be

the most convenient. We can pick any 2 macroscopic parameters, like

may not be

the most convenient. We can pick any 2 macroscopic parameters, like

and

and  , and then determine the others (e.g.,

, and then determine the others (e.g.,  and

and  ). To determine

the other macroscopic parameters, we need to know their relation to

the ones that we specified. Let us now derive these relations.

In doing so, we will define a number of useful quantities such as

enthalpy, the Helmholtz free energy and the Gibbs free energy.

). To determine

the other macroscopic parameters, we need to know their relation to

the ones that we specified. Let us now derive these relations.

In doing so, we will define a number of useful quantities such as

enthalpy, the Helmholtz free energy and the Gibbs free energy.

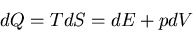

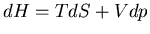

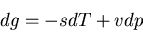

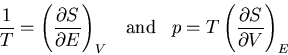

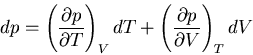

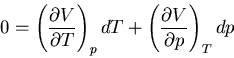

We start with the fundamental thermodynamic relation for a quasi-static

infinitesimal process:

|

(1) |

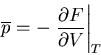

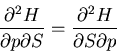

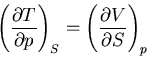

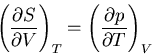

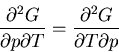

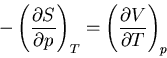

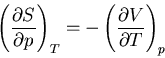

Summary of Maxwell relations and thermodynamic functions

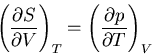

These are Maxwell's relations which we derived starting from the

fundamental relation

|

(42) |

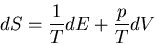

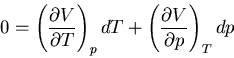

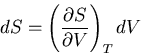

Notice that we can rewrite this

|

(43) |

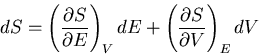

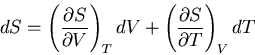

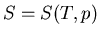

Since the entropy  is a state function,

is a state function,  is an exact differential

and we can write it as:

is an exact differential

and we can write it as:

|

(44) |

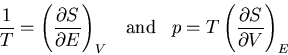

Comparing coefficients of  and

and  , we find

, we find

|

(45) |

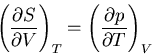

These are relations that we derived earlier. Recall

|

(46) |

and

|

(47) |

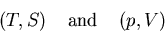

Note that the conjugate pairs of variables

|

(48) |

appear paired in (42) and when one cross multiplies the

Maxwell relations. In other words the numerator on one side is conjugate to

the denominator on the other side. To obtain the correct sign, note that

if the two variables with respect to which one differentiates are the same

variables  and

and  which occur as differentials in (42),

then the minus sign that occurs in (42) also occurs in the

Maxwell relation. Any one permutation away from these particular variables

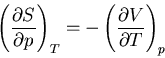

introduces a change of sign. For example, consider the Maxwell relation

(39)

with derivatives with respect to

which occur as differentials in (42),

then the minus sign that occurs in (42) also occurs in the

Maxwell relation. Any one permutation away from these particular variables

introduces a change of sign. For example, consider the Maxwell relation

(39)

with derivatives with respect to  and

and  . Switching from

. Switching from  to

to  implies one sign change with respect to the minus sign in (42);

hence there is a plus sign in (39).

implies one sign change with respect to the minus sign in (42);

hence there is a plus sign in (39).

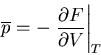

We also summarize the thermodynamic functions:

Notice that the conjugate variables are always paired up. The sign changes

when one changes the independent variable compared to the fundamental

relation (42).

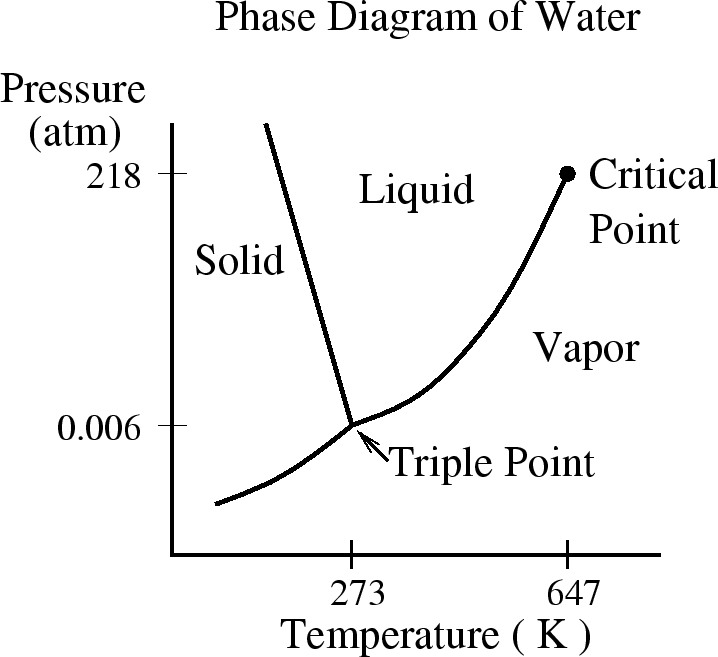

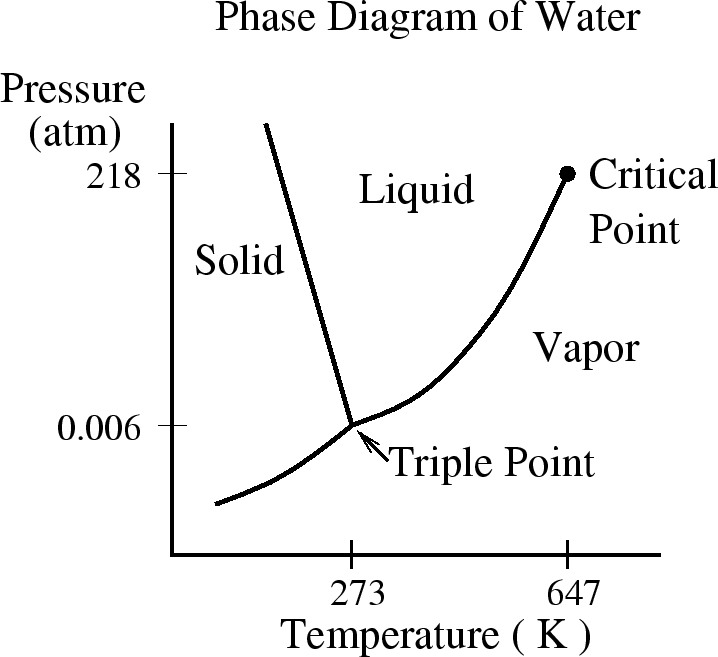

Phase Transitions and the Clausius-Clapeyron Equation

Let me try to give some idea of why these thermodynamic functions

are useful. We know from classical mechanics and electromagnetism

that energy is a very useful concept because it is conserved, and

because systems try to minimize their energy. Now we have ``generalized

energies'' such as  ,

,  , and

, and  . Chemists like enthalpy

because in the lab pressure rather than volume is kept constant.

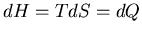

Note that

. Chemists like enthalpy

because in the lab pressure rather than volume is kept constant.

Note that  , so if pressure is constant which means

, so if pressure is constant which means

, then

, then  which is why enthalpy is thought of as heat.

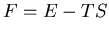

When physicists refer to free energy, they usually mean the Helmholtz

free energy

which is why enthalpy is thought of as heat.

When physicists refer to free energy, they usually mean the Helmholtz

free energy  because they can calculate this starting

from the Hamiltonian. However, experimentally it is the Gibbs free

energy

because they can calculate this starting

from the Hamiltonian. However, experimentally it is the Gibbs free

energy  that is relevant. Physicists often speak about

minimizing the

free energy. Consider water and ice. If we were to just consider

minimizing the internal energy

that is relevant. Physicists often speak about

minimizing the

free energy. Consider water and ice. If we were to just consider

minimizing the internal energy  which is the sum of the kinetic

and potential energies, then ice would be the lowest energy state.

Water molecules have less kinetic energy in ice than in water. Also

the water molecules are, on average, farther from each other in ice than

in water, so their potential energy of interaction is less in ice than

in water. But ice only exists at low temperatures. Why is that?

Because at high temperatures the free energy of water is lower than

that of ice. If we consider constant pressure and hence the Gibbs

free energy, then we want to minimize

which is the sum of the kinetic

and potential energies, then ice would be the lowest energy state.

Water molecules have less kinetic energy in ice than in water. Also

the water molecules are, on average, farther from each other in ice than

in water, so their potential energy of interaction is less in ice than

in water. But ice only exists at low temperatures. Why is that?

Because at high temperatures the free energy of water is lower than

that of ice. If we consider constant pressure and hence the Gibbs

free energy, then we want to minimize

|

(57) |

At high temperatures the second term  is important. Water molecules

have a much higher entropy in their liquid state than in their solid

state. More entropy means more microstates in phase space which improves

the chances of the system being in a liquid microstate. (Just like buying

more lottery tickets improves your chances of winning.)

The higher entropy of the liquid offsets the fact that

is important. Water molecules

have a much higher entropy in their liquid state than in their solid

state. More entropy means more microstates in phase space which improves

the chances of the system being in a liquid microstate. (Just like buying

more lottery tickets improves your chances of winning.)

The higher entropy of the liquid offsets the fact that

. At low

temperatures

. At low

temperatures  is less important, so

is less important, so

matters and the free energy for ice is lower than that of water. The

transition temperature

matters and the free energy for ice is lower than that of water. The

transition temperature  between ice and water is given by

between ice and water is given by

|

(58) |

We can actually use this relation to derive an interesting relation

called the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. Remember I told you that

water is unusual because ice expands and because the slope of the

phase boundary between ice and water is negative ( ). These

facts are related through the Clausius-Claperyon equation. (See Reif 8.5

for more details.)

). These

facts are related through the Clausius-Claperyon equation. (See Reif 8.5

for more details.)

=3.0 true in

|

(59) |

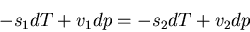

Here

is the Gibbs free energy per mole of phase

is the Gibbs free energy per mole of phase

at temperature

at temperature  and pressure

and pressure  . If we move a little ways along

the phase boundary, then we have

. If we move a little ways along

the phase boundary, then we have

|

(60) |

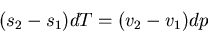

Subtracting these two equations leads to the condition:

|

(61) |

Now use (57)

|

(62) |

where  is the molar entropy and

is the molar entropy and  is the molar volume.

So (62) becomes

is the molar volume.

So (62) becomes

|

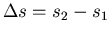

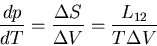

(63) |

|

(64) |

or

|

(65) |

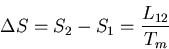

where

and

and

. This is called the

Clausius-Clapeyron equation. It relates the slope of the phase

boundary at a given point to the ratio of the entropy change

. This is called the

Clausius-Clapeyron equation. It relates the slope of the phase

boundary at a given point to the ratio of the entropy change

to the volume change

to the volume change  .

.

Let's apply this to

the water-ice transition. We know that the slope of the phase

boundary  . Let phase 1 be water and let phase 2 be ice.

Then

. Let phase 1 be water and let phase 2 be ice.

Then

since ice has less entropy

than water. Putting these 2 facts together in

the Clausius-Clapeyron equation implies that we must have

since ice has less entropy

than water. Putting these 2 facts together in

the Clausius-Clapeyron equation implies that we must have  .

Indeed water expands on freezing and

.

Indeed water expands on freezing and

.

So the unusual negative slope of the melting line means that water

expands on freezing. As we mentioned earlier, it also means that you

can cool down a water-ice mixture by pressurizing it and following

the coexistence curve, i.e., the melting line or phase boundary.

.

So the unusual negative slope of the melting line means that water

expands on freezing. As we mentioned earlier, it also means that you

can cool down a water-ice mixture by pressurizing it and following

the coexistence curve, i.e., the melting line or phase boundary.

Another example is  He which also has a melting line with a negative

slope. The fact that

He which also has a melting line with a negative

slope. The fact that  means that if you increase the pressure

on a mixture of liquid and solid

means that if you increase the pressure

on a mixture of liquid and solid  He, the temperature will drop. This

is the principle behind cooling with a Pomeranchuk cell. Unlike the case

of water where ice floats because it is less dense, solid

He, the temperature will drop. This

is the principle behind cooling with a Pomeranchuk cell. Unlike the case

of water where ice floats because it is less dense, solid  He sinks

because it is more dense than liquid

He sinks

because it is more dense than liquid  He. The Clausius-Clapeyron

equation then implies that

He. The Clausius-Clapeyron

equation then implies that

,

i.e., solid

,

i.e., solid  He has more entropy than liquid

He has more entropy than liquid  He! How can this be?

It turns out that it is spin entropy. A

He! How can this be?

It turns out that it is spin entropy. A  He atom is a fermion with a nuclear

spin 1/2. The atoms in liquid

He atom is a fermion with a nuclear

spin 1/2. The atoms in liquid  He roam around and their wavefunctions

overlap, so that liquid

He roam around and their wavefunctions

overlap, so that liquid  He has a Fermi sea just like electrons do.

The Fermi energy is lower if the

He has a Fermi sea just like electrons do.

The Fermi energy is lower if the  He atoms can pair up with opposite spins

so that two

He atoms can pair up with opposite spins

so that two  He atoms can occupy each translational energy state.

However, in solid liquid

He atoms can occupy each translational energy state.

However, in solid liquid  He, the atoms are centered on lattice

sites and the wavefunctions do not overlap much. So the spins on

different atoms in the solid are not correlated and the spin

entropy is

He, the atoms are centered on lattice

sites and the wavefunctions do not overlap much. So the spins on

different atoms in the solid are not correlated and the spin

entropy is  which is much larger than in the liquid.

which is much larger than in the liquid.

Now back to the general case. Since there is an entropy change associated with

the phase transformation from phase 1 to phase 2, heat must be absorbed

(or emitted). The ``latent heat of transformation''  is defined

as the heat absorbed when a given amount of phase 1 is transformed to

phase 2. For example, to melt a solid, you dump heat into it

until it

reaches the melting temperature. When it reaches the melting temperature,

its temperature stays at

is defined

as the heat absorbed when a given amount of phase 1 is transformed to

phase 2. For example, to melt a solid, you dump heat into it

until it

reaches the melting temperature. When it reaches the melting temperature,

its temperature stays at  even though you continue to dump in heat.

It uses the absorbed heat to transform the solid into liquid. This heat is

the latent heat

even though you continue to dump in heat.

It uses the absorbed heat to transform the solid into liquid. This heat is

the latent heat  .

Since the process takes place at the constant temperature

.

Since the process takes place at the constant temperature  , the

corresponding entropy change is simply

, the

corresponding entropy change is simply

|

(66) |

Thus the Clausius-Clapeyron equation (66) can be written

|

(67) |

If  refers to the molar volume, then

refers to the molar volume, then  is the latent

heat per mole; if

is the latent

heat per mole; if  refers to the volume per gram, then

refers to the volume per gram, then  is the latent heat per gram. In most substances, the latent heat

is used to melt the solid into a liquid. However, if you put

heat into liquid

is the latent heat per gram. In most substances, the latent heat

is used to melt the solid into a liquid. However, if you put

heat into liquid  He when it is on the melting line, it will

form solid because solid

He when it is on the melting line, it will

form solid because solid  He has more entropy than liquid

He has more entropy than liquid  He.

He.

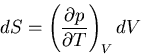

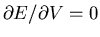

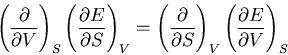

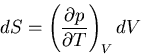

Examples of using the Maxwell relations

Let's give some examples where the Maxwell relations can be used.

Suppose we want to calculate

. We start

with our usual fundamental relation

. We start

with our usual fundamental relation

|

(68) |

We want to replace  with

with  . So we regard the entropy as a function

of the independent variables

. So we regard the entropy as a function

of the independent variables  and

and  :

:

|

(69) |

is an exact differential:

is an exact differential:

|

(70) |

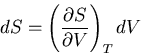

Since we are interested in

at constant

temperature,

at constant

temperature,  and

and

|

(71) |

Now use the Maxwell relation (40):

|

(72) |

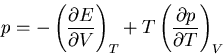

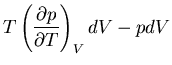

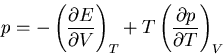

So we have

|

(73) |

and

Hence

|

(75) |

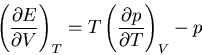

Let's take a moment to consider what this means physically. We know

that gas cools when it expands, and that the pressure rises when it

is heated. There must be some connection between these two

phenomena. Microscopically we can think of the kinetic energy of the

gas molecules. Macroscopically, eq. (76) gives the relation.

If we hold the volume fixed and increase the temperature, the pressure

rises at a rate

. Related to that fact is this:

if we increase the volume, the gas will cool unless we pour some heat

in to maintain the temperature, and

. Related to that fact is this:

if we increase the volume, the gas will cool unless we pour some heat

in to maintain the temperature, and

tells us the amount of heat needed to maintain the temperature.

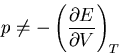

(Notice that for an ideal gas

tells us the amount of heat needed to maintain the temperature.

(Notice that for an ideal gas

.)

Equation (76) expresses

the fundamental relation between these two effects. Notice that we

didn't need to know the microscopic interactions between the gas

particles in order to deduce the relationship between the amount of heat

needed to maintain a constant temperature when the gas expands,

and the pressure change when the gas is heated. That's what thermodynamics

does; it gives us relationships between macroscopic quantities without

having to know about microscopics.

.)

Equation (76) expresses

the fundamental relation between these two effects. Notice that we

didn't need to know the microscopic interactions between the gas

particles in order to deduce the relationship between the amount of heat

needed to maintain a constant temperature when the gas expands,

and the pressure change when the gas is heated. That's what thermodynamics

does; it gives us relationships between macroscopic quantities without

having to know about microscopics.

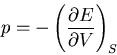

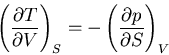

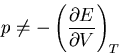

Aside: Notice that

|

(76) |

as one might expect. Rather

|

(77) |

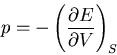

However,

|

(78) |

implies that

|

(79) |

It matters what is kept constant! Recall from (25) that

|

(80) |

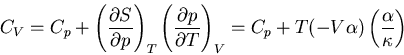

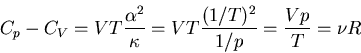

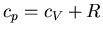

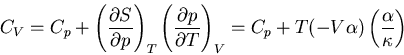

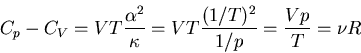

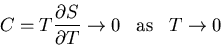

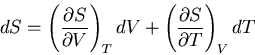

Specific Heats

Consider a homogeneous substance whose volume  is the only relevant

external parameter. We want the relation between the molar specific heat

is the only relevant

external parameter. We want the relation between the molar specific heat

at constant volume and the molar specific heat

at constant volume and the molar specific heat  at constant

pressure. We found this relation earlier for an ideal gas

(

at constant

pressure. We found this relation earlier for an ideal gas

( ), but now we want the general relation. This is a useful

relation because theoretical calculations are usually done at constant

volume and experimental measurements are done at constant pressure.

This is also a nice illustration of the usefulness of the Maxwell relations

and other identities and definitions.

), but now we want the general relation. This is a useful

relation because theoretical calculations are usually done at constant

volume and experimental measurements are done at constant pressure.

This is also a nice illustration of the usefulness of the Maxwell relations

and other identities and definitions.

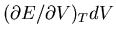

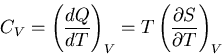

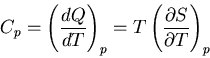

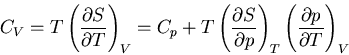

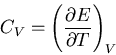

The heat capacity at constant volume is given by

|

(81) |

and the heat capacity at constant pressure is

|

(82) |

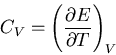

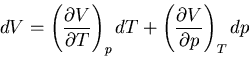

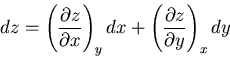

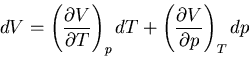

Let us consider the independent variables as  and

and  . Then

. Then  and

and

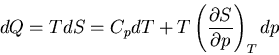

![\begin{displaymath}

dQ=TdS=T\left[\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_pdT+

\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial p}\right)_Tdp\right]

\end{displaymath}](img147.png) |

(83) |

Using (83), we have

|

(84) |

At constant pressure,  and we obtain (83). But to calculate

and we obtain (83). But to calculate

, we see from (82) that

, we see from (82) that  and

and  are the independent

variables. So we plug

are the independent

variables. So we plug

|

(85) |

into (85) to obtain

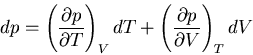

![\begin{displaymath}

dQ=TdS=C_pdT+T\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial p}\right)_T\l...

...t)_VdT+\left(\frac{\partial p}

{\partial V}\right)_T dV\right]

\end{displaymath}](img151.png) |

(86) |

Constant  means that

means that  and so

and so

|

(87) |

This is a relation between  and

and  but it involves derivatives

which are not easily measured. However we can use Maxwell's relations to

write this relation in terms of quantities that are measurable.

In particular (41) is

but it involves derivatives

which are not easily measured. However we can use Maxwell's relations to

write this relation in terms of quantities that are measurable.

In particular (41) is

|

(88) |

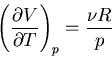

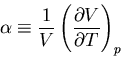

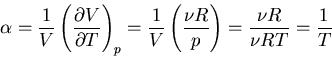

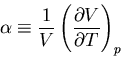

The change of volume with temperature at constant pressure is related to

the ``volume coefficient of expansion''  (sometimes called the

coefficient of thermal expansion):

(sometimes called the

coefficient of thermal expansion):

|

(89) |

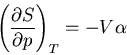

Thus

|

(90) |

The derivative

is also not easy to measure

since measurements at constant volume are difficult. It is easier to

control

is also not easy to measure

since measurements at constant volume are difficult. It is easier to

control  and

and  . So let's write

. So let's write

|

(91) |

For constant volume  and

and

|

(92) |

we can rearrange this get an expression for  :

:

|

(93) |

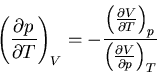

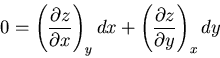

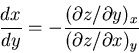

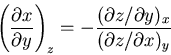

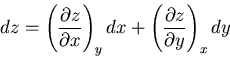

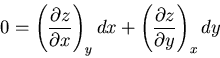

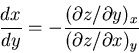

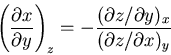

Aside:

This is an example of the general relation proved in Appendix 9. If we have

3 variables  ,

,  , and

, and  , two of which are independent, then we can

write, for example,

, two of which are independent, then we can

write, for example,

|

(94) |

and

|

(95) |

At constant  we have

we have  and

and

|

(96) |

Thus

|

(97) |

or, since  was kept constant

was kept constant

|

(98) |

This sort of relation between partial derivatives

is used extensively in thermodynamics.

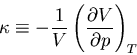

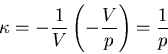

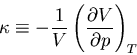

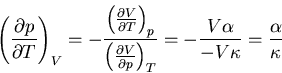

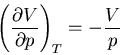

Returning to (94), we note that the numerator is related to

the expansion coefficient  . The denominator measures the change

in the volume of the substance with increasing pressure at constant

temperature. The change of the volume will be negative, since the volume

decreases with increasing pressure. We can define the ``isothermal

compressibility'' of the substance:

. The denominator measures the change

in the volume of the substance with increasing pressure at constant

temperature. The change of the volume will be negative, since the volume

decreases with increasing pressure. We can define the ``isothermal

compressibility'' of the substance:

|

(99) |

The compressibility is a measure of how squishy the substance is.

Hence (94) becomes

|

(100) |

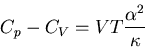

Plugging (91) and (101) into (88) yields

|

(101) |

or

|

(102) |

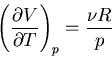

Let's test this formula on the simple case of an ideal gas. We start with

the equation of state:

|

(103) |

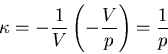

We need to calculate the expansion coefficient. For constant

|

(104) |

Hence

|

(105) |

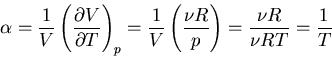

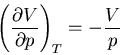

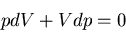

Next we calculate the compressibility  . At constant temperature

the equation of state yields

. At constant temperature

the equation of state yields

|

(106) |

Hence

|

(107) |

and

|

(108) |

Thus (103) becomes

|

(109) |

or, per mole,

|

(110) |

which agrees with our previous result.

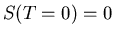

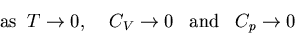

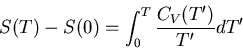

Limiting properties of the specific heat as

of a system smoothly approaches some limiting

constant

of a system smoothly approaches some limiting

constant  , independent of all parameters of the system. This is just

a statement that the number of states at low temperatures is very small.

In the case of a nondegenerate ground state, there is just one state and

, independent of all parameters of the system. This is just

a statement that the number of states at low temperatures is very small.

In the case of a nondegenerate ground state, there is just one state and

. So, in general,

. So, in general,

|

(111) |

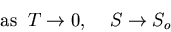

This implies that the derivative

remains finite

as

remains finite

as

. In other words, it does not go to infinity. (Technically

speaking, the derivatives appearing in (82) and (83)

remain finite as

. In other words, it does not go to infinity. (Technically

speaking, the derivatives appearing in (82) and (83)

remain finite as  goes to 0.) So one can conclude that the

heat capacity goes to 0 as

goes to 0.) So one can conclude that the

heat capacity goes to 0 as

:

:

|

(112) |

or more precisely,

|

(113) |

The fact that the heat capacity goes to 0 at zero temperature merely

reflects the fact that the system settles into its ground state as

. If we recall that

. If we recall that

|

(114) |

then reducing the temperature further will not change the energy since the

energy has bottomed out.

Notice that we need

as

as

in order

to guarantee proper convergence of the integral in

in order

to guarantee proper convergence of the integral in

|

(115) |

The entropy difference on the left must be finite, so the integral

must also be finite.

Next: About this document ...

Clare Yu

2007-04-25

![]() ). These

facts are related through the Clausius-Claperyon equation. (See Reif 8.5

for more details.)

). These

facts are related through the Clausius-Claperyon equation. (See Reif 8.5

for more details.)

![]() . Let phase 1 be water and let phase 2 be ice.

Then

. Let phase 1 be water and let phase 2 be ice.

Then

![]() since ice has less entropy

than water. Putting these 2 facts together in

the Clausius-Clapeyron equation implies that we must have

since ice has less entropy

than water. Putting these 2 facts together in

the Clausius-Clapeyron equation implies that we must have ![]() .

Indeed water expands on freezing and

.

Indeed water expands on freezing and

![]() .

So the unusual negative slope of the melting line means that water

expands on freezing. As we mentioned earlier, it also means that you

can cool down a water-ice mixture by pressurizing it and following

the coexistence curve, i.e., the melting line or phase boundary.

.

So the unusual negative slope of the melting line means that water

expands on freezing. As we mentioned earlier, it also means that you

can cool down a water-ice mixture by pressurizing it and following

the coexistence curve, i.e., the melting line or phase boundary.

![]() He which also has a melting line with a negative

slope. The fact that

He which also has a melting line with a negative

slope. The fact that ![]() means that if you increase the pressure

on a mixture of liquid and solid

means that if you increase the pressure

on a mixture of liquid and solid ![]() He, the temperature will drop. This

is the principle behind cooling with a Pomeranchuk cell. Unlike the case

of water where ice floats because it is less dense, solid

He, the temperature will drop. This

is the principle behind cooling with a Pomeranchuk cell. Unlike the case

of water where ice floats because it is less dense, solid ![]() He sinks

because it is more dense than liquid

He sinks

because it is more dense than liquid ![]() He. The Clausius-Clapeyron

equation then implies that

He. The Clausius-Clapeyron

equation then implies that

![]() ,

i.e., solid

,

i.e., solid ![]() He has more entropy than liquid

He has more entropy than liquid ![]() He! How can this be?

It turns out that it is spin entropy. A

He! How can this be?

It turns out that it is spin entropy. A ![]() He atom is a fermion with a nuclear

spin 1/2. The atoms in liquid

He atom is a fermion with a nuclear

spin 1/2. The atoms in liquid ![]() He roam around and their wavefunctions

overlap, so that liquid

He roam around and their wavefunctions

overlap, so that liquid ![]() He has a Fermi sea just like electrons do.

The Fermi energy is lower if the

He has a Fermi sea just like electrons do.

The Fermi energy is lower if the ![]() He atoms can pair up with opposite spins

so that two

He atoms can pair up with opposite spins

so that two ![]() He atoms can occupy each translational energy state.

However, in solid liquid

He atoms can occupy each translational energy state.

However, in solid liquid ![]() He, the atoms are centered on lattice

sites and the wavefunctions do not overlap much. So the spins on

different atoms in the solid are not correlated and the spin

entropy is

He, the atoms are centered on lattice

sites and the wavefunctions do not overlap much. So the spins on

different atoms in the solid are not correlated and the spin

entropy is ![]() which is much larger than in the liquid.

which is much larger than in the liquid.

![]() is defined

as the heat absorbed when a given amount of phase 1 is transformed to

phase 2. For example, to melt a solid, you dump heat into it

until it

reaches the melting temperature. When it reaches the melting temperature,

its temperature stays at

is defined

as the heat absorbed when a given amount of phase 1 is transformed to

phase 2. For example, to melt a solid, you dump heat into it

until it

reaches the melting temperature. When it reaches the melting temperature,

its temperature stays at ![]() even though you continue to dump in heat.

It uses the absorbed heat to transform the solid into liquid. This heat is

the latent heat

even though you continue to dump in heat.

It uses the absorbed heat to transform the solid into liquid. This heat is

the latent heat ![]() .

Since the process takes place at the constant temperature

.

Since the process takes place at the constant temperature ![]() , the

corresponding entropy change is simply

, the

corresponding entropy change is simply

![\begin{displaymath}

dQ=TdS=T\left[\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_pdT+

\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial p}\right)_Tdp\right]

\end{displaymath}](img147.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

dQ=TdS=C_pdT+T\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial p}\right)_T\l...

...t)_VdT+\left(\frac{\partial p}

{\partial V}\right)_T dV\right]

\end{displaymath}](img151.png)

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , two of which are independent, then we can

write, for example,

, two of which are independent, then we can

write, for example,

![]() . The denominator measures the change

in the volume of the substance with increasing pressure at constant

temperature. The change of the volume will be negative, since the volume

decreases with increasing pressure. We can define the ``isothermal

compressibility'' of the substance:

. The denominator measures the change

in the volume of the substance with increasing pressure at constant

temperature. The change of the volume will be negative, since the volume

decreases with increasing pressure. We can define the ``isothermal

compressibility'' of the substance: