We know that Newton’s laws of motion hold and are invariant in inertial frames of reference that are related by the Galilean transformation. But it is the Lorentz transformation rather than the Galilean transformation that is correct. That means that the laws of classical mechanics cannot be correct, and we must find new laws of relativistic mechanics.

In doing so, we will be guided by 3 principles:

Classically, momentum is defined by

| (1) |

where m and  the mass and velocity of an object. What is the correct relativistic definition of

momentum? We have the freedom to define momentum any way we like, but to be

useful, we would like to define it such that total momentum is conserved in all inertial

frames.

the mass and velocity of an object. What is the correct relativistic definition of

momentum? We have the freedom to define momentum any way we like, but to be

useful, we would like to define it such that total momentum is conserved in all inertial

frames.

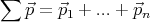

Recall the law of momentum conservation. If there are n bodies with momenta  1, ...,

1, ...,  n,

then, in the absence of external forces, the total momentum is given by

n,

then, in the absence of external forces, the total momentum is given by

| (2) |

cannot change. We would like to define momentum relativistically to preserve conservation of momentum.

As your book describes in section 2.3, we can’t use the classical definition Eq. (1) because of the way velocity transforms between reference frames. For example, the way uy transforms in going from S to S′ depends on u x. The classical definition of momentum is

| (3) |

The problem is that both  and t are subject to the Lorentz transformation and that makes

things messy.

and t are subject to the Lorentz transformation and that makes

things messy.

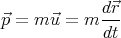

The relativistic way to define momentum is

| (4) |

where t0 is the proper time, i.e., the time measured in the rest frame of the particle or object. Notice that with this definition,

| (5) |

which is invariant when one goes between reference frames that are moving relative to one another along the x-axis. That is because t0 is invariant and y = y′. Similarly for pz.

Since dt = γdt0 where γ = 1∕ , we can write

, we can write

| (6) |

A constant force changes the momentum and hence the velocity. Notice that as u → c, γ and hence p increase without limit, but the speed u never reaches the speed of light (see plot of u versus p in Fig 2.2 of your book). Thus no object can go faster than the speed of light.

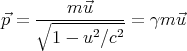

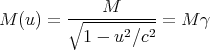

We can define a relativistic mass M(u) by

| (7) |

Your book calls this a variable mass mvar, but it doesn’t want to use this. However, it does make it easy to write the momentum in the traditional form

| (8) |

Notice from Eq. (7) that if the speed u of an object with nonzero mass is equal to the speed of light, the relativistic mass is infinity. If the object’s speed exceeds the speed of light, then the relativistic mass M(u) is imaginary. Clearly, this is absurd and so, once again, the velocity of an object cannot exceed the speed of light. If the object has mass, it cannot travel at the speed of light; its speed must be less than the speed of light.

Now we need to define a relativistic energy. We will use 2 criteria:

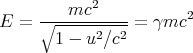

The relativistic energy that satisfies these requirements turns out to be

| (9) |

This applies to any single body, no matter how big or how small. Notice that the units are right. (It’s always important to check units.) γ is dimensionless, and mc2 has units of energy. (Recall that kinetic energy is (1∕2)mv2.)

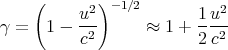

Now let’s take the nonrelativistic (slow) limit u ≪ c. Then

| (10) |

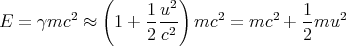

Therefore, when u ≪ c,

| (11) |

The first term is a constant independent of the speed u, and we can always add a constant to the energy since we can set the zero of the energy (E = 0) anywhere. The second term is just the usual classical expression for the kinetic energy. So our definition of the relativistic energy satisfies the criterion of reducing to the classical kinetic energy in the nonrelativistic (slow) limit.

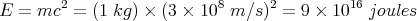

Now let’s look at that constant mc2. If the object is at rest, then u = 0, γ = 1, and Eq. (9) reduces to the famous equation

| (12) |

This is called the rest energy of the mass m. If we could convert a mass m completely into energy, then this is the amount of energy we would get. It’s a lot of energy because the speed of light c is so large, and c2 is even larger. For example, the rest energy of a 1 kg lump of metal is

| (13) |

which is about the energy generated by a large power plant in one year. E = mc2 is the basic equation behind nuclear power, and atomic bombs. These are powered by nuclear fission in which, typically, uranium 235 nuclei are split apart, converting about 1/1000 of the rest energy into heat. Thus 1 kg of 235U can yield a fantastic amount of heat (9 × 1013 J).

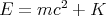

When an object is not at rest, its energy E = γmc2 is the sum of its rest energy mc2 plus its kinetic energy K = (E - mc2):

| (14) |

where

| (15) |

In the nonrelativistic limit K ≈ mu2, the classical kinetic energy. However, in the relativistic

limit of u → c, we get something quite different. Because γ can approach infinity, K can

approach infinity even though the speed u can never reach the speed of light c. Notice that K,

like its classical counterpart, is always positive (K ≥ 0).

mu2, the classical kinetic energy. However, in the relativistic

limit of u → c, we get something quite different. Because γ can approach infinity, K can

approach infinity even though the speed u can never reach the speed of light c. Notice that K,

like its classical counterpart, is always positive (K ≥ 0).

| (16) |

and

| (17) |

If we divide Eq. (16) by Eq. (17), we obtain

| (18) |

or

| (19) |

which give the dimensionless velocity  =

=  ∕c in terms of

∕c in terms of  and E. Notice that

and E. Notice that  c has

dimensions of energy, so the ratio

c has

dimensions of energy, so the ratio  c∕E is dimensionless, just like

c∕E is dimensionless, just like  . Eq. (19) is one useful

relation.

. Eq. (19) is one useful

relation.

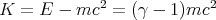

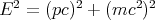

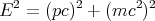

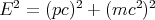

The other is

| (20) |

This has the same form as the Pythagorean relation for a right triangle with sides pc and mc2 and hypotenuse E, though there isn’t any deep meaning to this. To show that this is correct, we can plug in E = γmc2 and p = γmv, solve for γ2 and show that this reduces to the definition γ2 = (1 - v2∕c2)-1.

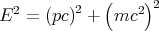

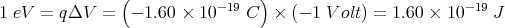

| (21) |

Typical atomic energies are on the order of 1 eV or so, while those in nuclear physics are on the order of 106 eV = 1 MeV.

Masses of particles are often given in eV with the understanding that they are referring to the rest energy mc2. Techically, the mass is properly in units of eV/c2. So, for example, the “mass” of the electron is given as 0.511 MeV, meaning mc2 = 0.511 MeV. Similarly, when momentum p is given in units of MeV, they really mean the quantity pc, or the units of [p] is eV/c.

If you look up a table for the mass of atoms, the mass is often given in atomic mass units (denoted u). The conversion is

| (22) |

The famous equation E = mc2 implies that if you can convert mass into energy, then you would get a lot of energy because the speed of light squared is so big. So does matter get converted to energy? The answer is yes. An example where this happens for atomic nuclei is when atomic nuclei break apart, either because they are unstable (radioactive) or because they are forced apart by an incoming particle (e.g., a neutron) in a process called fission. This is the principle behind atomic power plants like San Onofre.

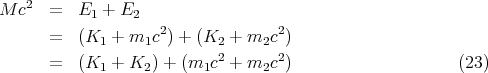

Let’s suppose that a nucleus at rest has a mass M, so that the initial energy is Mc2. Then suppose the nucleus breaks apart due to radioactive decay in which pieces of the nucleus go flying apart. The energy then is a combination of the kinetic energy K of the pieces and their rest energy. Suppose that the nucleus breaks into 2 pieces. Since total energy (including the rest mass energy) is conserved, we have

| (24) |

The missing mass is converted into the kinetic energy of the fragments flying apart:

| (25) |

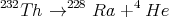

For example, your book considers the radioactive decay of 232Th via the reaction

| (26) |

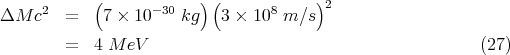

The sum of the masses of 228Ra and 4He nuclei is 0.004 u smaller than the original 232Th nucleus. Since 1 u = 1.66 × 10-27 kg, this corresponds to 7 × 10-30 kg. This missing mass is converted into kinetic energy because the products (228Ra and 4He) fly apart. The amount of kinetic energy is

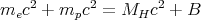

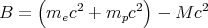

So sometimes we need to add energy to merge or fuse 2 pieces together. However, sometimes, the opposite can happen. In particular, energy can be released when 2 things are brought together to form a more stable (lower energy) thing. For example, if we bring together an electron and a proton to form a hydrogen atom, then 13.6 eV is released. This is called the binding energy since is the amount of energy that would be required to pull apart the proton and electron in a hydrogen atom. If we add the mass me of a free electron (free means it is floating around, and is not bound inside an atom), and the mass mp a free proton, the sum is 13.6 eV/c2 greater than the mass M H of a hydrogen atom. This is another example of mass being converted into energy. In symbols:

| (28) |

where B is the binding energy. So the binding energy corresponds to the rest energy of the missing mass:

| (29) |

Similarly, when atoms are combined to form stable molecules, binding energy is released. Energy is also released when nuclei are forced together to form bigger stable nuclei in a process called fusion. For example, 4 hydrogen atoms can be fused to make 1 helium atom. This releases binding energy. This is what powers the sun and hydrogen bombs.

The Λ particle is a subatomic particle that can spontaneously decay into a proton and a negatively charged pion.

| (30) |

The sum of the mass of the proton and the pion will be less than that of the Λ. In a certain experiment, the outgoing particles were traveling in the +x direction with momenta pp = 581 MeV/c and pπ=256 MeV/c. The rest masses are mp = 938 Mev/c2 and m π = 140 MeV/c2. Find the rest mass mΛ of the Λ.

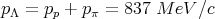

To solve this problem, let us start with

| (31) |

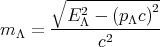

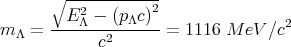

Solving for the mass of the Λ gives

| (32) |

So we need the energy and the momentum of the Λ to find the mass. First we find the energy using Eq. (31)

| (33) |

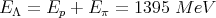

This gives Ep = 1103 MeV and Eπ = 292 MeV. So

| (34) |

Conservation of momentum gives

| (35) |

where the momenta are all pointing along the positive x axis. Now that we know EΛ and pΛ, we can Eq. (32) to find the mass:

| (36) |

This is how many masses of unstable subatomic particles are measured.

| (37) |

and

| (38) |

These are equivalent because p = mu, so dp∕dt = ma. But in relativity, p = γmu, so dp∕dt≠ma. In relativity, the most convenient definition of force turns out to be

| (39) |

Example 2.9 shows that this definition of force allows the work-energy theorem to remain valid. Namely,

| (40) |

This says that if a mass m, acted on by a force F, moves a small distance dr, the change in its energy, dE, equals the work done by F.

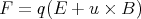

This definition of force allows us to keep the Lorentz force law intact:

| (41) |

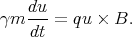

One easy application of this equation is when a particle with charge q moves with velocity u perpendicular to a uniform field B. The particle’s energy is constant because no work is done on it. To see this, look at the work-energy theorem. It turns out that the force is perpendicular to the direction of motion of the particle because the particle moves in a circle and the force points radially in towards the center of the circle. Therefore, since the energy (E = γmc2) is constant, the velocity is constant in magnitude and only changes direction. To see that it moves in a circle, start with

| (42) |

which we can write as

| (43) |

Use acceleration a = du∕dt and the fact that u is perpendicular to B to write

| (44) |

For motion in a circle of radius R, the centripetal acceleration a = u2∕R. The reason is the same in relativity as in classical mechanics. Using γmu = p, we can solve for R and write

| (45) |

or

| (46) |

This provides a convenient way to measure the momentum of a particle of known charge q. We know the applied field B and we can measure the radius R of the circle.

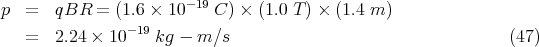

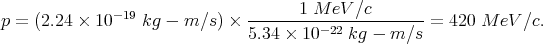

For example, suppose we want to find the momentum of a proton moving perpendicular to a uniform magnetic field B = 1.0 tesla (T) in a circle of radius 1.4 m. We plug this into Eq. (46) using q = e = 1.6 × 10-19 C. This gives

| (48) |

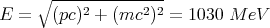

Since the proton’s rest mass is known to be m = 938 MeV/c2, we can find its energy from the “Pythagorean relation” to be

| (49) |

It’s better to go back to

| (50) |

and

| (51) |

If m = 0, then these equations reduce to

| (52) |

and

| (53) |

So the massless particle travels at the speed of light. Conversely, if we discovered a particle that traveled at speed c, then β = u∕c would equal 1=pc∕E. That would mean E = pc and hence, that m = 0, i.e., it would be a massless particle. So massless particles travel at the speed of light, and particles that travel at c must be massless. Particles with nonzero mass must travel at less than the speed of light.

Do massless particles exist? Yes. The best known massless particle is the photon which is a particle of light. As we will discuss more later, light can be described in 2 ways: (1) as an electromagnetic wave, and (2) as particles or packets of energy called photons.

To find the energy and momentum of a massless particle, we look at a reaction that it is involved in, e.g., photoionization of hydrogen in which a photon hits the electron in a hydrogen atom, causing the electron to be ejected:

| (54) |

where γ is the symbol for a photon. We measure the momentum and energy of the particles with mass, then use conservation of energy to deduce the energy and momentum of the massless particle.

Another example of a massless particle is the graviton but there is no experimental evidence for the graviton. It used be accepted that the neutrino had no mass, but now there is experimental evidence that it does have a little bit of mass.

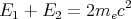

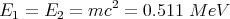

You’ve probably heard that when matter and antimatter collide, they annihilate and release a lot of energy. The positron is an anti-electron, i.e., it’s the antimatter version of an electron. It is exactly like an electron except that it has a positive charge (+e). The positron has the same mass as an electron. Suppose a positron and an electron are both at rest with no momentum. So they only have their rest mass energies: mec2 and m pc2 = m ec2. Then when they annihilate, 2 photons are produced. Conservation of momentum requires that their total momentum is zero, and the sum of their total energy is 2mec2:

| (55) |

and

| (56) |

So the photons that are created must have equal and opposite momenta:

| (57) |

Since E = pc for photons, the photons must have equal energies: E1 = E2, and

| (58) |

So all the rest mass energy is converted into electromagnetic energy.

Positrons are used in PET scans. PET stands for Positron Emission Tomography. This is a medical diagnostic probe in which a patient is injected with a radioactive positron emitter (like carbon 11) in a suitably chosen solution like glucose (sugar) that will tend to collect in the brain, for example. Once in the brain, the emitted positrons annihilate with nearby electrons, and photons are emitted that are detected by a ring of detectors. In this way, it is possible to create an accurate map of the areas of interest.

The relativistic equations all reduce to their classical counterparts in the limit of low speeds (v ≪ c). When should one use the relativistic formulae and when is it good enough to use the classical equations? There is no clear-cut answer. It depends on what you need it for. For example, GPS (Global Positioning System) needs an accuracy of 1 ns, so relativistic effects must be taken into account. Table 2.4 of your book compares the values of the kinetic energy calculated with relativistic and classical formulas for various values of the velocity. As a general rule of thumb, you can ignore relativisitic effect if the speeds are 0.1c or less, or if a particle’s kinetic energy K is much less than 1% of its rest energy. (Recall that K goes as u2, so this is why a speed of 0.1c corresponds to 0.01% of the energy.) For speeds greater than 0.1c or kinetic energies greater than 0.01mc2, relativistic effects probably need to be taken into account, and relativistic equations should probably be used.